The Year 1904 in Film: A Watershed Year

0This is a work in progress as I am still researching the year 1904 in film. I’ve added 386 films to my index so far whereas IMDb has 1,831 entries. I think I may have, however, found most of the surviving films. Conclusions drawn will be based on the data I’ve gathered so far and this article will be revised as my research continues.

Out of those 385 films, 71 were released in France, and 32 of those by Pathé frères, 31 by Georges Méliès, 2 from the Lumière Brothers, 2 by filmmakers Alfred Mulsant and Célestin Chevalier, 3 by Gaumont and one by an unknown filmmaker. So far the USA is ahead with 253 films, 74 of which were released by the Edison company and 168 by American Mutoscope & Biograph (AM&B). The remaining 11 films were released by Paley & Steiner, Siegmund Lubin, Percival L. Waters, Selig Polyscope Company and one unknown company.

There are 51 films produced in the UK, four from the Charles Urban Trading Company, one from the Williamson Kinematograph Company, eight from the Hepworth Manufacturing Company, two from William Haggar and Sons, 13 from the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation, one from the Warwick Trading Company, six from Paul’s Animatograph Works, seven from Mitchell & Kenyon, one each from the Salvation Army Cinematograph, George Albert Smith Films, Arnold Muir Wilson, Conservative and Unionist Film Association, Cricks & Sharp, which began producing films in 1904, and four from the Clarendon Film Company. So far I have six films from Germany and one film each from Italy, Switzerland, Canada and Spain.

My YouTube playlist contains 205 films of which six are incomplete. Of the remaining 180 films in my index, one, Cohen’s Advertising Scheme, is only available on DVD, Boxing Horses, Luna Park, Coney Island can’t be uploaded to YouTube due to their policies regarding content involving animals but may be viewed on my Odnoklassniki channel, one is available on screenonline.org which unfortunately is restricted to registered universities and libraries, another is available on player.bfi.org which unfortunately is only available to residents of the UK, 135 are held in the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection which haven’t been digitized and made available for viewing, 22 are held in various archives and 19 films are presumed lost (this number will certainly grow as my research continues).

Significant Events and Films of the Year

According to an article about the “Century of Cinema: 1904” program during Il Cinema Ritrovato’s 2024 film festival, “1904 is a watershed, the pivotal year in which everything that went before had not yet disappeared and in which everything that was to come had already made its appearance.” The article also states that it is “a year that easily goes unnoticed and that for some mysterious reason seems to have left little trace.” I searched through my index for directors and production companies that made their debuts in 1904 and only found one production company, Cricks and Sharp, founded by George Howard Cricks and Henry Martin Sharp. In 1908 Cricks partnered with John Howard Martin to form Cricks and Martin. In the USA 1904 saw the humble beginnings of what would become two major theatre chains, Fox and Loews, which will be covered more extensively below. Though significant events in the film industry may be few there are several significant films produced during the year and a significant event in world history, namely the Russo-Japanese War, which was the topic of several films.

Any Good Idea Is Worth Stealing

As the quote above says, the year was a mix of “everything that went before”, actualities, newsreels, trick and féerie films and “everything that was to come”, narrative films which were increasingly in demand since the success of Edwin Porter’s The Great Train Robbery released in 1903. In fact Siegmund Lubin, who often pirated Edison’s and others’ films, produced his own version of The Great Train Robbery in 1904 in order to cash in on the trend.

Other companies weren’t above plagiarism. In August American Mutoscope & Biograph released Personal which is about a wealthy young man who advertises for a wife in the newspaper and ends up getting chased by a horde of women. In September Edison released their version of the story with How a French Nobleman Got a Wife Through the New York Herald Personal Columns. Lubin released his version, Meet Me at the Fountain in November and in December Segundo de Chomon’s version, El Heredero de Casa Pruna was released in Spain. The idea has been reworked several times since then including the 1916 play, Seven Chances, which Buster Keaton adapted for the screen in 1925.

The Buster Brown Series Continues

Speaking of Buster Keaton, Porter continued the Buster Brown series of films begun in the Fall of 1903. Buster Brown was a a comic-strip character created in 1902 by Richard F. Outcault. At the time Buster Keaton was a popular child actor in vaudeville which may have influenced Outcault to choose the name for his character. Out of the seven Buster films from 1904, six are in the playlist and the seventh, Pranks of Buster Brown and His Dog Tige, is held in the paper print collection of the Library of Congress.

Le Voyage à travers l’impossible

Le Voyage à travers l’impossible, also known as The Impossible Voyage, is a trick film directed by Georges Méliès. Inspired by Jules Verne’s 1882 play of the same name, and modeled in style and format on Méliès’s highly successful 1902 film Le voyage dans la lune, the film is a satire of scientific exploration in which a group of geographically-minded tourists attempt a journey to the sun using various methods of transportation. The film was a significant international success at the time of its release.

Production took place during the summer of 1904. The film, with a length of 374 meters (about 20 minutes at silent-film projection speeds), was Méliès’s longest to date, and cost about ₣37,500 (US $7,500) to make. In its staging and design, the film is symmetrical with Le voyage dans la lune: while the astronomers’ progress toward the moon in that film is consistently depicted as left-to-right motion, the Institute of Incoherent Geography’s progress toward the sun in Voyage à travers l’impossible is consistently right-to-left. While most of the film was shot inside Méliès’s glass studio, the scene at the foot of the Jungfrau was filmed outdoors, in the garden of Méliès’s property in Montreuil, Seine-Saint-Denis. The factory set in the second scene recalls the Hall des Machines at the Paris Exposition of 1900. Techniques used for special effects include stage machinery (including scenery rolling horizontally and vertically), pyrotechnics, miniature effects, substitution splices, and dissolves.

Voyage à travers l’impossible was one of the most popular films of the first few years of the twentieth century, rivaled only by similar Méliès films such as Le Royaume des fées (1903) and the massively successful Le voyage dans la lune. The film critic Lewis Jacobs said of the film:

This film expressed all of Méliès’s talents. In it his feeling for caricature, painting, theatrical invention and camera science became triumphant. The complexity of his tricks, his resourcefulness with mechanical contrivances, the imaginativeness of the settings and the sumptuous tableaux made the film a masterpiece for its day.

Film scholar Elizabeth Ezra highlights the film’s sharp social satire, noting how the rich but inept members of the Institute “wreak havoc wherever they go, disrupting the lives of bucolic mountain climbers, alpine villagers, factory workers and sailors,” and arguing that this conflict between upper classes and working classes is mirrored by other contrasts in the film (heat and ice, sun and sea, and so on).

Reference: Wikipedia

The Coronation of King Peter the First

The longest film from 1904 by far is The Coronation of King Peter the First which runs for an hour and 16 minutes. Other versions on YouTube run 54 minutes but I believe the frame rate is too fast and have slowed it down. It was filmed in Belgrade, Serbia by two Englishmen, Frank Mottershaw and Arnold Muir Wilson, and is one of the oldest extant films made in the Balkans. It was Serbia’s last and only modern coronation. In June 1903 (actually 29 May at the time, as Serbia was still following the old Julian Calendar), King Alexander Obrenovich and his wife Queen Draga Mashin were assassinated in Belgrade. The throne passed to the Karadyordyevic dynasty, and the new king, Peter I Karadyordyevic, was crowned in September 1904, more than a year after the coup d’état. Belgrade invited foreign guests to the coronation, but no European court (except Montenegro) sent representatives, as Serbia was under sanctions because of the 1903 killing of the royal family. Serbia became a part of the state of Yugoslavia after World War I, but Peter did not hold a second coronation and neither of his two successors, the Yugoslav monarchs Alexander and Peter II, were crowned. This was due to the religious diversity of the new state.

References: History-Film-History

Inside an American Factory: Films of the Westinghouse Works

The Westinghouse Works Collection contains 21 actuality films showing various views of Westinghouse companies. Most prominently featured are the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, and the Westinghouse Machine Company. The films were intended to showcase the company’s operations. Exterior and interior shots of the factories are shown along with scenes of male and female workers performing their duties at the plants.

The motion pictures taken of the Westinghouse Works were produced by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company from April 13 to May 16, 1904, and were photographed by G. W. (Billy) Bitzer. Views of much of the Westinghouse Works are shown in a panorama shot taken from a moving crane along with long shots of aisles of machinery.

The films were shown daily with great success in the Westinghouse Auditorium at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis in 1904. Although little production information is available for these films, they may have been made expressly for use at the Exposition. This would not have been unusual since AM&B is known to have produced other films for the Exposition for the U.S. Department of Interior. A catalog for the AM&B company indicates that at least 29 films were made of the Westinghouse Works of which 21 are included the playlist.

The films of the Westinghouse Works were the first made successfully using the Cooper Hewitt Mercury Vapor Lamp which was manufactured by the Cooper Hewitt Electric Company, a Westinghouse company based in New York. Since the lamp was made by Westinghouse and was later featured prominently in advertising for AM&B films, it is possible that there may have been a special arrangement between the two companies–perhaps motion pictures in exchange for lamps, or photographing the Westinghouse Works as a test run for the use of the lamp. Unfortunately, in the absence of source material, these theories are mere speculation.

A review of the Westinghouse Works motion pictures was offered in the Pittsburgh Post on May 12, 1904 after a special viewing of them was held at Carnegie Hall. An excerpt of the article read as follows:

To satisfy the curiosity of the Westinghouse employees who were desirous of seeing the views to be sent to the Louisiana Purchase exposition, an exhibition of them was given last night by the Westinghouse officials at Carnegie music hall. The moving pictures show the interiors of the four Westinghouse plants at East Pittsburg, Swissvale, Wilmerding and Trafford City, combined with a panoramic view of the country between those places. The interior views are the first successful ones taken since the invention of the Cooper Hewitt vaporized mercury lamp, which in this instance made the clearest and brightest moving picture ever exhibited. Besides the numerous pictures of employees and their work, there were numerous humorous scenes interspersed by the Mutoscope company, who made the films for the Westinghouse people.

Reference: Library of Congress

The Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was fought between the Japanese Empire and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1905 over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. Russia sought a warm-water port on the Pacific Ocean both for its navy and for maritime trade. Vladivostok, Russia’s main naval base on the Pacific Ocean since 1872, remained ice-free and operational only during the summer; Port Arthur, a naval base in Liaodong Province leased to Russia by the Qing dynasty of China from 1897, was operational year round.

Russia had pursued an expansionist policy east of the Urals, in Siberia and the Far East, since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. Since the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan had feared Russian encroachment would interfere with its plans to establish a sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria. Seeing Russia as a rival, Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of the Korean Empire as being within the Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused and demanded the establishment of a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan in Korea, north of the 39th parallel. The Imperial Japanese Government perceived this as obstructing their plans for expansion into mainland Asia and chose to go to war. After negotiations broke down in 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy opened hostilities in a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur, China on February 8-9, 1904. The Russian Empire responded by declaring war on Japan.

Films about the Spanish–American War, the Second Boer War and the Boxer Rebellion had proven popular with audiences and several production companies sought to capitalize on this new conflict. Since Hong Kong at the time was a British colony it’s not surprising that British film companies were the first to produce films on the war though some films were reconstructions filmed in the UK. The Hepworth Manufacturing Company, the Warwick Trading Company and the Charles Urban Trading Company had been regularly producing films shot in the Far East before the war began.

Battle of Port Arthur

Perhaps the first film released about the war was Warwick’s Torpedo Attack at Port Arthur. It was released February 27 and is a lost film as far as I can tell but described in their catalogue as a “Russian Cruiser firing guns at torpedo boat.” Urban released The Bombardment of Port Arthur on March 26, a reenactment by the British Navy at Portsmouth which is also lost.

Also in March the Selig Polyscope Company and AM&B released reenactments of battles, probably the first American companies to do so. Selig reenacted the events of February 8-9 with The Attack on Port Arthur. A copy is held by the Library of Congress in the paper print collection and described as toy boats in a table top lake. AM&B’s The Battle of the Yalu, according to the Library of Congress, was filmed in Manlius, New York, on March 16, and March 18 with students of St. John’s Military Academy. I’m not sure which battle this refers to since the Battle of the Yalu River, the first major land offensive of the war, began on April 30. Perhaps it was a minor battle.

Pathé frères released Événements Russo-Japonais : Combat naval russo-japonais in March, the first installment of their series of 16 films on the war. An announcement in their catalogue read:

We have sent to the Far East an operator [Lucien Nonguet] to take Views on the scenes of the Russian-Japanese War; however, like the competitors, we are obliged to bring before the public immediately some films relating to the actual state of affairs, and we have arranged accordingly some of our films. On this order we show a film which can be given as “A Russian-Japanese Naval Fight” [Combat naval russo-japonais] although this is not taken on the spot. As to the others, they have been taken from nature. All these, under the circumstances, should be great favourites with the public.

This film is extant and was projected at the 2024 Cinema Ritrovato Film Festival. A couple other films from the series appear below.

Battle of Chemulpo Bay

On February 9 the Imperial Japanese Navy completed its attack of the Russian Pacific Fleet at Chemulpo Bay. In April Porter filmed Battle of Chemulpo Bay, another reenactment. The Edison summary reads as follows:

Shows the crew of a Japanese battleship working a gun during the engagement of Chemulpo Bay. The Russian cruiser “Variag,” and gunboat “Koreitz,” are seen coming out of the harbor. As soon as they appear in the open sea they are attacked by the Japanese fleet, and after receiving a fierce fire from the enemy’s guns, they endeavor to return to port, but both sink before reaching the bay.

Porter also filmed Skirmish Between Russian and Japanese Advance Guards on April 4, 1904 in Forest Hill, New Jersey. Someone at the Library of Congress has described it as a “renactment of a skirmish that was likely to have occurred in the Russo-Japanese War.” The summary in the Edison catalogue reads as follows:

The foreground shows a detachment of Japanese soldiers with a Gatling gun on top of a hill. The officer in command orders a drill. Just as the drill is finished a detachment of Russians is seen coming over an adjoining hill, and immediately an engagement takes place. The gun is run into position; but despite the heavy fire of the Japs, they are defeated by the Russians; the bombs thrown in their midst doing deadly work. The Russians are next seen capturing the gun and ammunition. They are soon surprised by a second detachment of Japanese and compelled to retreat.

Gaumont British Picture Corporation released Bombardment of Port Arthur on May 28. Most likely this is also a reenactment filmed with British Navy ships.

Événements Russo-Japonais (Autour de Port-Arthur) : Deuxième série, part of Pathé’s series of films on the war mentioned previously, was included in their catalogue supplement of August, 1904. It depicts, as the title suggests, a battle near Port Arthur. The film consisted of two scenes, an attack on a hill, a fragment of which appears below, and a scene depicting the removal of the wounded from the battlefield which is missing.

Battle of Liaoyang

The Battle of Liaoyang, a key encounter midway through the Russo-Japanese War, took place from August 24 to September 3, 1904. “No fighting so fierce, so sustained, and so bloody has been experienced since the armies of Grant and Lee met in their great death grapple in the Wilderness in the Civil War”, wrote Sidney Tyler in his 1905 book The Japan-Russia War. On September 6 the Japanese occupied the Yentai Mines to the north of Liaoyang according to Tyler, which is depicted in the Pathé film below.

Less than three weeks after the battle, Biograph had completed The Hero of Liao Yang. Below is a synopsis from their catalogue:

A young Japanese officer interrupted from the quiet pleasures of his home life by official notice to join his regiment at once, swears fealty to his Emperor on the sword of his ancestor, and in a characteristically unemotional way bids farewell to his wife and children. The following scenes find him at the front, where he is intrusted with a deed of desperate daring – the carrying of a message through the enemy’s country to the commander of the second Japanese army. In the accomplishment of this feat he is severely wounded and captured by Cossacks, but, though seriously wounded, manages to devour the paper upon which the despatch is written. He is taken to a Russian field hospital, and there, by feigning death and with the assistance of a faithful Chinese coolie, escapes and arrives at the headquarters of the second army while the ‘Battle of Liao-Yang’ is raging. In the midst of terrific cannonading and shells bursting about in every direction, he hands his despatch to the officer commanding and is decorated upon the field with the emblem of highest honor in Japan, taken from the breast of the general himself.

As Gregory A. Waller points out in his article Narrating the new Japan: Biograph’s The Hero of Liao-Yang (1904), “if this film seen today seems truncated, discontinuous or bafflingly incoherent, this is in part because The Hero of Liao-Yang was only fully realized and ‘completed’ (narratively as well as politically and ideologically) at the site of exhibition rather than the site of production.” Viewers of films from this era would do well to bear this in mind.

Finally, here is a collection of nine unidentified films about the war held by the British Film Institute. These are not included in the Year 1904 in Film playlist.

Louisiana Purchase Exposition

In 1904, from April 30 to December 1, St. Louis hosted a World’s Fair to celebrate the centennial of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. More than 60 countries and 43 of the then-45 American states maintained exhibition spaces at the fair, which was attended by nearly 19.7 million people. Historians generally emphasize the prominence of the themes of race and imperialism, and the fair’s long-lasting impact on intellectuals in the fields of history, art history, architecture and anthropology. From the point of view of the memory of the average person who attended the fair, it primarily promoted entertainment, consumer goods and popular culture. The monumental Greco-Roman architecture of this and other fairs of the era did much to influence permanent new buildings and master plans of major cities. I’ve included 12 films shot at the fair by AM&B’s cameraman A.E. Weed in my film index, six of which are in the YouTube playlist.

Reference: Wikipedia

William Fox Enters the Film Business

Wilhelm Fuchs, better known as William Fox, was born January 1, 1879 in the town of Tulchva in what was then Austria-Hungary. His parents were German Jews who brought their young son to New York City when he was only nine months old. With his family largely destitute, William found himself as a youth forced to sell candy in Central Park, work as a newsboy and in the fur and garment industry. He started his own fur business in 1900, which he sold in order to start the Greater New York Film Rental Company in 1904 with the purchase of a run-down Nickelodeon in Brooklyn. As the new owner with an empty house, Fox hired a coin manipulator and a barker to attract patrons into the dark 146-seat theater. Once audiences adequately understood what moving pictures were, live acts were dispensed with. More theaters were opened and he became a successful film exhibitor. Fox opened a projection style theater at New York’s 700 Broadway during May 1906. With its success, he purchased more Nickelodeons and converted them into theaters.

With his fledgling chain of theaters, Fox fought against the movie monopoly of the Motion Picture Patents Company owned by Thomas Edison. The fight ended in 1912 when the Supreme Court ruled in Fox’s favor. Fox then founded Fox Films, which on average produced four feature films a year. Beginning in 1914, New Jersey-based Fox bought films outright from the Balboa Amusement Producing Company in Long Beach, California, for distribution to his own theaters and then for rental to other theaters across the country. He formed the Fox Film Corporation on February 1, 1915. The company’s first film studio was leased in Fort Lee, New Jersey, where many other early film studios were based at the beginning of the 20th century. He now had the capital to acquire facilities and expand his production capacity. The production company moved to 13 acres in Hollywood California, where many movie companies were relocating. Between 1915 and 1919, Fox would rake in millions of dollars through films which featured Fox Film’s first breakout star Theda Bara, known as “The Vamp”, for her performance in A Fool There Was (1915).

In 1925–1926, Fox purchased the rights to the work of Freeman Harrison Owens, the U.S. rights to the Tri-Ergon system invented by three German inventors, Josef Engl (1893–1942), Hans Vogt (1890–1979), and Joseph Massolle (1889–1957), and the work of Theodore Case to create the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system, introduced in 1927 with the release of F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. Sound-on-film systems such as Movietone and RCA Photophone soon became the standard, and competing sound-on-disc technologies, such as Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone, became obsolete. From 1928 to 1964, Fox Movietone News was one of the major newsreel series in the U.S. Despite the fact that his film studio was based in Hollywood, Fox opted to instead remain in New York and was more familiar with his financiers than with either his movie makers or movie stars.

Following the 1927 death of Marcus Loew, head of Loews Incorporated, the parent company of rival studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, control of MGM passed to his longtime associate, Nicholas Schenck. Fox saw an opportunity to expand his empire, and in 1929, with Schenck’s assent, bought the Loew family’s MGM holdings, unbeknownst to MGM studio bosses Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg. Mayer and Thalberg were outraged; despite their high posts at MGM, they were not shareholders. Mayer used his strong political connections to persuade the Justice Department to sue Fox for violating federal antitrust laws. In July 1929, Fox was severely injured in an automobile accident. By the time he recovered, the stock market crash in October 1929 had wiped out virtually his entire fortune, ending any chance of the Loews-Fox merger going through even if the Justice Department had approved it.

Fox lost control of his organization in 1930 during a hostile takeover. In 1935, Fox Film Corporation would merge with 20th Century Pictures, becoming 20th Century-Fox. William Fox was never connected with the ownership, production or management of the movie studio that famously bore his name. A combination of the stock market crash, Fox’s car accident injuries, and government antitrust action, forced him into a protracted seven-year legal battle to stave off bankruptcy. At his bankruptcy hearing in 1936, he attempted to bribe judge John Warren Davis and committed perjury. In 1943, Fox served a five-month and seventeen day prison sentence on charges of conspiring to obstruct justice and defraud the United States, in connection with his bankruptcy. Years after his prison release, U.S. President Harry Truman would grant Fox a Presidential pardon.

For many years, Fox resented the way that Wall Street had forced him from control of his company. In 1933, he collaborated with the writer Upton Sinclair on a book Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox in which Fox recounted his life, and stating his views on what he considered to be a large Wall Street conspiracy against him. Fox died in 1952 at the age of 73. His death went largely unnoticed by the film industry; no one from Hollywood attended his funeral.

References: Hal Doby and Wikipedia

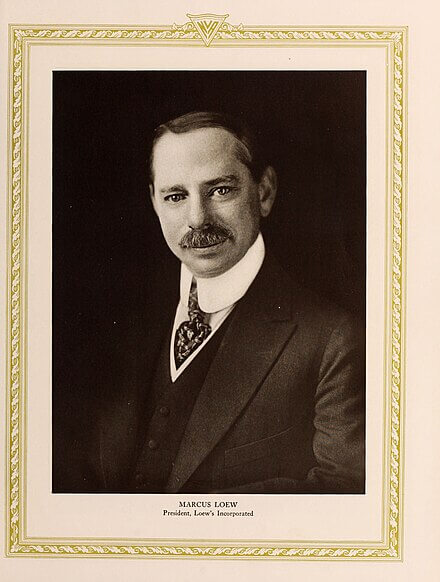

Marcus Loew Begins His Theatre Chain

Loew was born May 7, 1870 in New York City, into a poor Jewish family, who had emigrated to New York City a few years previously from Austria and Germany. He was forced by circumstances to work at a very young age and had little formal education. Beginning with a small amount of money saved from menial jobs, he invested in the penny arcade business. Shortly after, in partnership with Adolph Zukor and others, he founded the successful but short-lived Automatic Vaudeville Company which established a chain of arcades across several cities. After the company dissolved in 1904 he founded the People’s Vaudeville Company, a theater chain showcasing one-reel films and live variety shows. In 1910, the company had considerably expanded and was renamed Loew’s Consolidated Enterprises. His associates included Adolph Zukor, Joseph Schenck, and Nicholas Schenck. In addition to theaters, Loew and the Schencks expanded the Fort George Amusement Park in upper Manhattan.

Eventually Loew found himself faced with a serious dilemma: his merged companies lacked a central managerial command structure. Loew preferred to remain in New York overseeing the growing chain of Loew’s Theatres. Film production had been gravitating toward southern California since 1913. In 1919, Loew reorganized the company under the name Loew’s, Inc.

In 1920, Loew purchased Metro Pictures Corporation. A few years later, he acquired a controlling interest in the financially troubled Goldwyn Picture Corporation which at that point was controlled by theater impresario Lee Shubert. Goldwyn Pictures owned the “Leo the Lion” trademark and studio property in Culver City, California. But without its founder Samuel Goldwyn, the Goldwyn studio lacked strong management. With Loew’s vice president Nicholas Schenck needed in New York City to help manage the large East Coast movie theater operations, Loew had to find a qualified executive to take charge of this new Los Angeles entity.

Loew recalled meeting a film producer named Louis B. Mayer who had been operating a successful, modest studio in east Los Angeles. Mayer had been making low budget melodramas for a number of years, marketing them primarily to women. Since he rented most of his equipment and hired most of his stars on a per-picture basis, Loew wasn’t after Mayer’s brick and mortar business; he wanted Mayer and his Chief of Production, the former Universal Pictures executive, Irving Thalberg. Nicholas Schenck was dispatched to finalize the deal that ultimately resulted in the formation of Metro-Goldwyn Pictures in April 1924 with Mayer as the studio head and Thalberg chief of production.

Mayer’s company folded into Metro Goldwyn with two notable additions: Mayer Pictures’ contracts with key directors such as Fred Niblo and John M. Stahl, and up-and-coming actress Norma Shearer, later married to Thalberg. Mayer would eventually be rewarded by having his name added to the company. Loews Inc. would act as MGM’s financier and retain controlling interest for decades.

Though MGM was immediately successful, Loew died in 1927 of a heart attack at the age of 57 at his country home in Glen Cove, New York. Reporting his death, Variety called him “the most beloved man of all show business of all time”.

Reference: Wikipedia

Births

Many famous actors, directors and a cinematographer were born in 1904:

January 10 – Ray Bolger, actor, dancer, singer (d. 1987)

January 18 – Cary Grant, actor (d. 1986)

April 14 – John Gielgud, actor (d. 2000)

Ma7 17 – Jean Gabin, actor (d. 1976)

May 21 – Robert Montgomery, actor (d. 1981)

May 29 – Gregg Toland, cinematographer (d. 1948)

June 26 – Peter Lorre (d. 1964)

October 22 – Constance Bennett, actress, producer (d. 1965)

November 14 – Dick Powell, actor, musician, producer, director, studio head (d. 1963)

See Wikipedia for the complete list.

Deaths

May 8 – Eadweard Muybridge, chronophotographer (born 1830)

Film Journals Founded in 1904

The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal (London), 1904-05

Reference: domitor.org

The Playlist

The films are arranged in chronological order of release date but films for which the month and day of release cannot be determined appear at the beginning of the playlist in alphabetical order. The total running time of the playlist is nearly 12 hours. Click “Watch on YouTube” to see all the films in the playlist.

Next article in this series: The Year 1905 in Film.

Previous article in this series: The Year 1897 in Film