Early Film Pioneers: Alfred Clark and the Birth of the Historical Reconstruction Film

0One of the most remarkable cinematic innovations (technically and artistically) effected by the Edison Manufacturing Company in 1895 seems to have come about more or less by happenstance and to have passed almost completely unnoticed in the U.S. itself. By August, Raff and Gammon, the firm primarily responsible for marketing Edison films and equipment in America, faced by Edison’s continued refusal to abandon the notion of the “peephole” viewer and investigate the possibilities of projection, were becoming increasingly alarmed at the continuing decline in sales and the resultant decline in film-production. They urged the development of new subjects and Edison assigned the task to one Alfred Clark. Clark (1873-1950) does not seem to have been, as Charles Musser suggests, a Raff and Gammon employee, but an employee of the Edison Phonograph Company. He had previously worked for Edison’s chief rival, the North American Phonograph Company, which Edison destroyed with his habitual dirty tricks and legal chicanery. His main interest was in sound recording, an area in which he was something of an expert.

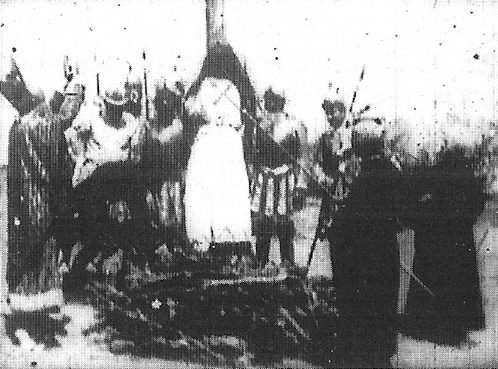

Imaginatively Clark made two films for Edison in August 1895, both based on dramatic historical scenes, Joan of Arc, showing the burning of the French heroine, and The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, which made a very early use of the stop-action technique to film the beheading of the queen (played, not as Charles Musser states, by a man, but by the wife of Robert Thomas, secretary and treasurer of the Kinetoscope Company). Presumably, however, it was not Clark himself, but the regular Edison cameraman, William Heise, who was actually responsible for the filming, but nothing in Heise’s previous or subsequent career, suggests that he would have had the imagination to conceive such films and it seems reasonable to suppose that, in this sense, Clark was the “director”. He and Heise also made Duel Between Two Historical Characters and three scenes from U.S. history, Rescue of Capt. John Smith by Pocahontas, Indian Scalping Scene, and A Frontier Scene (later retitled Lynching Scene). Of Clark’s films, only The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots and Joan of Arc, both filmed on August 28, 1895, appear to survive. A copy of Joan of Arc (at eighteen seconds in length probably pretty much the whole film), is preserved in an archive in Canada, and concentrates not so much on the burning of the French captive but on the torture she was submitted to at the stake. When shown in Spain and Portugal it was actually known as “The Torture of Joan of Arc” (O suplício de Joana d’Arc, Suplício de Juana d’Arc). It looks rather more like a US lynching, a subject Clark had also filmed, than the burning of a medieval heretic. Surprisingly perhaps no performance of the film is known in France, especially in the light of the films on the same subject that would be made there 1897-1899; perhaps there was a certain resentment of a non-French version of their own national heroine.

The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, on the other hand, was seemingly a very popular film, particularly in the French fairgrounds. It (or a film of the same name) was shown in Arras on 8 July 1896 by an exhibitor purporting to be “Le Cinématographe” (almost certainly the ubiquitous Henri Joly). It was shown, again by Joly, in Saint Quentin on the 8 September (as La Décapitation d’une femme) and in Nîmes on 14 November. In 1897 it was even shown in Havana, Cuba. One French newspaper, L’Indpendant des Pyrrénées Orientales, found it a moving spectacle – “La hache se lève, le sang jaillit, la tête roule sur le sol et le bourreau la saisit aux cheveux pour la montrer à son entourage” (The axe is raised, blood spurts, the head rolls on the ground and the executioner seizes it by the hair to show to those around him). Good wholesome family entertainment, in other words. In the light of this, one has to be a little skeptical of Georges Méliès’ claim (or acceptance of the claim) to have invented the technique of “stop-motion” or to have stumbled across the idea accidentally. He may very well have known Clark’s film.

Clark’s experiments in historical reconstruction mark an interesting departure but seemingly met with little favor. Clark himself went to France in 1899 as an Edison representative, but left the company to found his own Compagnie de Gramophone Française. He subsequently settled in Britain where he became chairman of the newly-formed EMI and was, in his spare time, a celebrated collector of Chinese ceramics. His innovative concept of the historical film was never followed up but left, like so many other ideas, for the French and Italians to develop further.

Gabriel Antoine Veyre (1871-1936), the Lumière operator in Latin America, based from August 1896 in Mexico, is exceptional amongst the Lumière cameramen abroad in that, from the outset, he experimented with films that are “fictional” in the sense of being staged reconstructions. The most famous, Un duelo a pistola en el bosque de Chapultepec (Un duel au pistolet à Mexico), a reconstruction of a duel between two Mexican deputies, was filmed in December 1896 and must have been amongst the very first batch of films dispatched by Veyre since it was already on show in France before the end of the month. The film, when it was shown in Mexico, caused some outcry in the press there, not, as is so often foolishly repeated, because people could not tell the difference between the real and the fictional but, on the contrary, precisely because they could tell the difference and were uneasy at the ethical implications of a non-explicit blurring of the two, especially in a situation where dueling had, according to historian Angel Escudero (El Duelo en Mexico, 1936), shown a dramatic increase in Mexico during the 1890s (24 duels as opposed to ten in the previous decade and just two in the 1870s). As regards the duel between Romero and “Veraza” (actually Verástegui), Francisco Romero was a highly experienced duelist and Verástegui was killed. In fact, however, this duel and the publicity surrounding it (and Veyre’s film) seems to have reversed the trend and led to a decline in the passion for dueling.

Veyre had earlier (October 1896) filmed the execution by firing-squad of a soldier convicted of treason, a film known variously as Proceso del soldado Antonio Navarro and La ejecuci del soldado Antonio Navarro. This was not a reconstruction but a genuine topicality. Despite the confusing multiplication of titles, the subject seems to have very much the execution rather than the trial, to which a camera would hardly have been admitted. The journal The Mexican Herald, after initially reporting that a “series of views were taken” as the prisoner and the firing squad were marching past (13 October 1896), gave further details four days later:

The owners of the Cinematograph Lumiére, took views of the execution of the soldier, Antonio Navarro, from the moment that the Lawyer Gonzalez Suarez delivered the handkerchief to the priest, Clemente, Miro so that the good father might bandage the eyes that were taking their last look at the sun, the views continuing until the poor fellow fell in death. It is said that the views taken were perfect, and will soon be publicly exhibited. The proceeds of the first exhibition will be devoted to the family of the executed soldier.

It is possible that Veyre had also shot, or intended to shoot, some form of reconstruction of the trial in which case the film would very clearly have prefigured other future docufictional accounts of contemporary executions such as the Mitchell and Kenyon Beheading of a Chinese Boxer (1900), Edwin S. Porter’s The Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison (1901). Peter Elfelt’s Henrettelsen (1903) or the gruesome Pathé series Exécutions capitales, also 1903, six films showing distinctive scenes of execution from all round the world (USA, Britain, France, Germany, Spain and China).

Execution was itself after all a kind of performance art. The last public hanging took place in Britain as long ago as 1868 but the last in the US did not take place until in 1897 and informal “justice” continued to provide regular lynchings that attracted crowds and generated souvenir postcards. The last public execution by guillotine in France took place in 1937. More innocently, one might also associate the genre with one of cinema’s major sister-arts, if not always recognized as such, the waxwork exhibition with its typical “chamber of horrors”.

This film also caused controversy, which, in the context of Veyre’s closeness to the Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz (1876-1911), gave very legitimate grounds for qualms. The “perfect” film was in the event never shown and completely disappeared from view; it is not even mentioned in Veyre’s voluble and detailed correspondence with his mother.

There is both a liking for the picturesque and a flamboyant taste for adventure but also something distinctly exploitative about Veyre’s film-making which is similarly apparent in the very marked “orientalism” of his films later shot in the Far East. Nevertheless, although one should necessarily disregard the role played by the « concessionnaire » and Veyre’s titular boss, the rather shadowy Argentinian, Claude Ferdinand Bon Bernard, the fact that Veyre made such films at all (and so early in his time abroad) suggests that, although a Lumière employee and a chemist by training, he must, as well as being a fine photographer, have already gained some knowledge of the world of cinema beyond the provincial confines of Lyon before leaving France.

Un duel au pistolet was a popular film, as witness a second duel scene (Un duel au pistolet II) which was shot by someone back in France, where dueling was also enjoying a certain vogue, possibly in the autumn of 1897 when Veyre was himself briefly there before setting off for his next assignment in Japan. A historical scene, Duel Between Two Historical Characters had been made by Alfred Clark and William Heise for Edison in 1895 and Veyre’s Proceso del soldado Antonio Navarro also puts one in mind not only of Clark and Heise’s Joan of Arc and The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, but also of a whole series of historical execution scenes made at about this time by Hatot and Breteau for Lumière (Mort de Robespierre, Mort de Charles Ier, and Exécution de Jeanne d’Arc, all filmed in 1897. Georges Méliès too would later claim to have made his first film of the life of Jeanne d’Arc in 1897.

Author David Bond is a historian who specializes in the study of cultural history. Subjects of interest, past and present, include late seventeenth-century English drama, early English paperback publishing, the French graphic novel (bande dessinnée), Jamaican popular music (not just the “r” word) and cinema – of all periods and all traditions but with a special interest in the period prior to the (mitigated) disaster of what is popularly known as “sound”.