The First Talkies – Part 1: 1900 “Le Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”

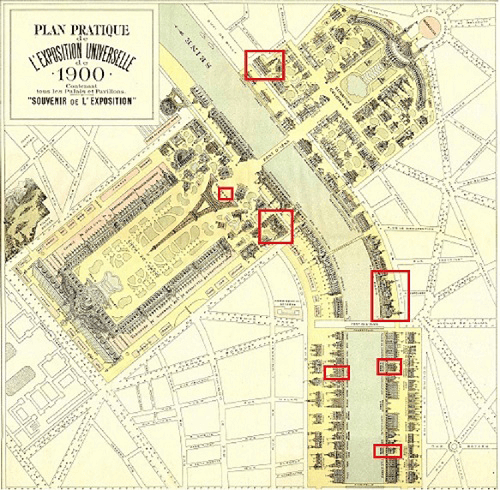

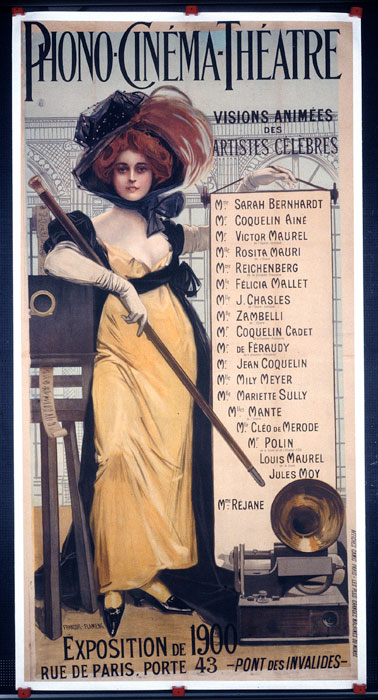

7Some of the most important early developments in “talking pictures” were stimulated by the Paris Exposition of 1900. One of the most notable cinematic events at the Exposition was the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” financed by Paris businessman Paul Decauville (1846-1922) with actress and dancer Marguerite Vrignault, later known as Marguerite Vrignault Chenu, (1861-c. 1933), apparently the original inspiration of the project, as directrice artistique, the term used at this period for what, broadly speaking, would now be simply described as the director. A limited company (société anonyme), La Société Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre, was formed on 2 March 1900 and the films were shot by photographer and cinematographer Clément-Maurice, using the “Cinépar” camera created by Ambrose-François Parnaland (1854-1913). Sound was provided by the “Idéal” phonographe of Henri Lioret (1848-1838), advertised, in competition with the Columbia’s Phonograph Company of Washington’s “Graphophone Multiplex Grand”, as “le plus grand phonographe du monde” (the largest phonograph in the world) but this was later replaced (September 19th) by the Pathé phonographe “Le Céleste”. Lioret was also responsible for the system of “playback” sound-synchronization. The pavilion at the Exposition, in the rue de Paris, was built by the architect René Dulong (1860-1944), and was based on Ange-Jacques Gabriel’s Pavilion frais (1751) in the Petit Trianon at Versailles. The décors were by the painter François Flameng (1856-1923), who also designed the magnificent poster showing Sarah Bernhardt in costume as Tosca, although no such scene was actually filmed for the show. The system of sound-synchronisation was fairly basic and relied essentially on the dexterity of the operator. According to Le Figaro (7 July 1900), the theatre had two exhibition-halls. In one the operator was former Lumière operator Félix Mesguich:

“Pour les projections parlantes, installation était également très simple. Devant l’écran, à la place de l’orchestre, se trouvaient deux petits boxes pour le phonographe et les appareils à bruit. Dans le cornet du phonographe, il y avait un microphone qui prenait le son, qu’un tube acoustique amenait à la cabine de l’opérateur, Félix Mesguich. Une lampe rouge s’allumait au déclenchement du cylindre phonographique pour permettre le départ simultané du film. L’opérateur, au moyen d’un casque ou d’un simple cornet acoustique, avait le son dans l’oreille : il réglait alors sa manivelle au son et tournait plus ou moins vite pour que les paroles ou les bruits tombassent « juste ».

For the talking picture, installation was also very simple. In front of the screen, in the orchestra pit, there were two small boxes for the phonograph and the sound instruments. In the horn of the phonograph, there was a microphone which picked up the sound, which passed through an acoustic tube that led to the cabin of the operator, Félix Mesguich. A red lamp lit up once the phonographic cylinder started to permit the simultaneous commencement of the film. The operator, by means of a headphone or a simple acoustic horn was able to hear the sound and regulated the movement of the crank, turning slower or faster so that the words and sounds came out ‘right’.”

-Henry Cossira (son of Émile), “La Résurrection du Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, L’image, nº 55, 31 mars 1933.

In the second hall, projection was in the hands of Clément-Maurice’s sons, Georges and Léopold. Here too the synchronisation, according to Léopold Maurice, was “approximatif” and he, as the younger and less experienced of the two, had difficulty in matching his cranking to the rhythm of the words and sound (pour suivre le son en accélérant ou ralentissant le projecteur). (Léopold Maurice in Bulletin de l’Association Française des Ingénieurs et Techniciens du Cinéma No 29, 1969).

Clément Maurice Gratioulet known as Clément-Maurice (1853-1933) was an ex-employee of the Lumière photographic factory at Monplaisir, Lyon and a close friend of Antoine Lumière and his sons, who had subsequently established himself in 1894 as a successful professional photographer in Paris with a studio at 8, boulevard des Italiens in Paris rented for him by Antoine Lumière, just above Georges Méliès’ théâtre Robert-Houdin. It was he who had arranged the rental of the Salon Indien, at the Grand Café, for the first public Lumière show on 28 December 1895, and who took charge of the till for the first performances. Clément-Maurice remained the official Paris concessionnaire for the Lumières and continued to manage the programme at the Grand Café until 10 April 1899, when, with the agreement of Louis Lumière, he resigned as concessionnaire and the offices at 8, boulevard des Italiens were sold. Clément-Maurice produced some of his finest photography at this time (Paris en plein air, a number of fine townscapes that were his contribution to the series Le Beau Pays de France in 1897) and he remained active as a independent cinematographer, organizing a series of projections to accompany a talk on cycling in 1897, making films for Gaumont in 1897-98 and in March of that year winning first prize in the world’s first film competition, held in Monaco, for his film Monaco vivant par les appareils cinématographiques. Since 1898 he had also worked, with the assistance of his teenage son Leopold, as a cinematographer, alongside Ambroise-François Parnaland, for the surgeon Eugène-Louis Doyen for the filming of his operations. In 1899 he was officially chosen by Doyen in preference to Parnaland to continue the work and the two would make over sixty films between 1899 and 1906.

In later years Marguerite Vrignault, now known as Chenu, related to singer Henry Cossira, son of the singer, the origins of the project:

Deux ans avant l’ouverture de l’Exposition de 1900, m’a rappelé Mme Chenu, j’avais, au cours d’un déjeuner de chasse chez Paul Decauville, fait allusion à l’intérêt qu’il y aurait à reconstituer en des visions animées le jeu et la voix de nos plus grands artistes. Séduit, Paul Decauville, m’encouragea à réaliser mon idée et monta une société anonyme dont il voulut prendre le conseil d’administration. Je pus donc faire contruire mon pavillon et, m’étant adressée aux frères Lumière, ceux-ci me conseillèrent de prendre Clément Maurice comme opérateur. Je retrouvai Maurice qui travaillait avec le docteur Doyen, et je n’eus pas à le regretter, car c’était un véritable artiste.

Two years before the opening of the 1900 Exposition, Mme Chenu recalled, I had, in the course of a hunt-breakfast at the house of Paul Decauville, referred to the interest in putting together animated pictures, performance and voice, of our greatest artistes. Convinced, Decauville encouraged me to put my idea into practice and formed a company of which he became president. I was able to have the pavilion built and, applying to the Lumière brothers, was recommended to employ Clément Maurice as operator. I found him working for Doctor Doyen and had no cause to regret the choice, as he was a real artist.”

-Henry Cossira, “La Résurrection du Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, L’image, nº 55, 31 mars 1933.

Vrignault’s highly ambitious programme consisted of over thirty synchronized sounds films, many hand-colored. There were songs, monologues, comic sketches and extracts from plays, operas and ballets featuring artistes such as Sarah Bernhardt, Coquelin, Gabriel Réjane, Rosita Mauri, Carlotta Zambelle, Cléo de Mérode, Foottit and Chocolat, Little Tich and many others. The films, all but a handful of which survive, several with their original sound cylinders, were long for the period (in practice two films of just over a minute long played continuously), each being nearly three minutes (between 2 minutes 30 seconds and three minutes) in all. The entire show, according to one contemporary review ran for between two and two and a half hours, although this relates to the touring show which probably contained a good deal of additional material. The running time of the original would presumably have been somewhat variable since there were two exhibition halls but probably no more than about an hour and a half altogether (forty-five minutes in each venue if the division between them was equal) and perhaps shorter still. One contemporary poster lists just six films: La Korrigane, L’Enfant prodigue, Le Cid, Hamlet, Danse javanaise and Chanson en crinoline, a twenty-minutes programme, although it is possible that further pieces, comic monologues and sketches, were used as “intermèdes” (interludes). Showing a selection in this way meant that the programme could be constantly varied; it was apparently changed every Friday. Another programme again lists just six pieces (Danse Directoire, La Poupée, Le Cygne, Les Précieuses ridicules, crossed out on the programme, La Korrigane and Chanson en Crinoline), with another six (Hamlet, Cyrano de Bergerac, Falstaff, Le Rêve and La Poupée announced for the following week. The “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” opened on 29 April 1900.

Theatre

L’Enfant prodigue – Ma Cousine

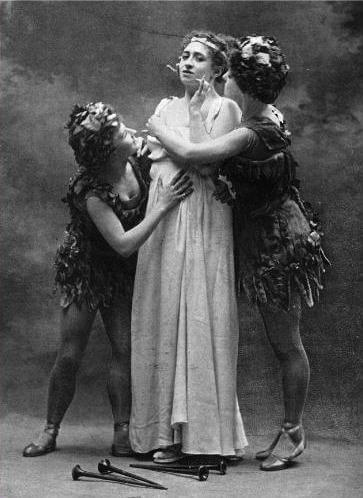

Amongst the theatrical scenes, there was a three-tableau excerpt from the pantomime L’Enfant prodigue (“Le Vol”, “Pierrot chez Phrynette” and “Le Retour”) by Michel-Antoine Carré also known as Michel Carré fils (1865-1945), adapted from his three-act stage-play of 1890 of the same name with music by André Wormser (1851-1926) starring Félicia Mallet as Pierrot and Marie Magnier as Madame Pierrot, his mother. Carré, the son of a well-known playwright and librettist, Michel Carré (1821-1872), had followed in his father’s footsteps. L’Enfant prodigue, probably his best-known work, was a major success both in France and internationally and was frequently revived with different casts. Félicia Mallet (1863-1928) was from the stage cast at the théâtre de Bouffes, having replaced Charlotte Raynard in the part. Magnier (1848-1913) had replaced Clémentine Schmidt and Irma Crosnier in the part of the mother. The part of Phrynette, created by Paula Lemière but later played on the stage by Francesca Zanfretta and Biana Duhamel (1870-1910) was advertised intriguingly on this occasion as being played by “Mlle X”. One would like to think that the part was perhaps played on this occasion by Biana’s little sister Sarah (1873-1926), who, as Rosalie and Pétronille, would later be a major star of early film comedy. The part of Pierrot père had been created by Adolphe Berthet and then played by Louis-Philippe Courtès (1833-1903) in the stage production but here it is played by another very distinguished actor, Edmond Duquesne (1849-1918). Duquesne would appear in over forty films 1909-1921, most notably playing Napoléon in André Calmettes’ 1911 film version of Victorien Sardou and Émile Moreau’s Madame Sans Gêne opposite Gabrielle Réjane in the title role, both playing the parts they had originally created on the stage in 1893.

Mallet’s natural style of pantomime was much admired. The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) compared her favorably to a certain Mlle Litini who enjoyed considerable success during the 1890s in the character of Pierrot in Tendres Aveux at l’Opéra and A Pierrot’s Life at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London. Two superb pastels of Litini, Le Miroir de Pierrot and Tendre Aveu, Melle Litini et Melle Bariaux, de l’Opéra by Pierre Carrier-Belleuse (1851-1933) were exhibited during the 1900 Exposition but Shaw’s preference for Mallet was firmly expressed in his Dramatic Opinions and Essays (1913):

Felicia Mallet is much more credible, much more realistic, and therefore much more intelligible – also much less slim, and not quite so youthful. Litini was like a dissolute “La Sylphide”: Mallet is frankly and heartily like a scion of the very smallest bourgeoisie sowing his wild oats. She is a good observer, a smart executant, and a vigorous and sympathetic actress, apparently quite indifferent to romantic charm, and intent only on the dramatic interest, realistic illusion, and comic force of her work. And she avoids the conventional gesture-code of academic Italian pantomime, depending on popularly graphic methods throughout.”

The Mlle X, playing Phrynette, gained an equally anonymous rich admirer during the run of the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”. In November, when the Exposition had ended and the show had transferred to the boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle Paris, the following advertisement appeared in Le Matin (22 November 1900):

MONSIEUR bien élevé, instruit, très riche, encore jeune, désirant se marier, voudrait faire connaissance d’une personne ressemblant à l’artiste qui mime le rôle de Phrynette dans L’Enfant prodigue, au Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre, 42 bis, boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle. Ecrire poste restante, sous initiales, T.M., bureau de la Madeleine.

GENTLEMAN, well mannered, educated, very rich, still young, wishing to marry, would like to make the acquaintance of someone resembling the artiste who mimes the role of Phrynette in L’Enfant prodigue, at the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre, 42 bis, boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle. Write poste restante, under the initials T.M., bureau de la Madeleine.”

The three scenes from the pantomime shown for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” represent the theft of money from the family safe by Pierrot while his parents sleep (“Le Vol”), the difficulties of his subsequent life with Phrynette (“Pierrot chez Phrynette”), a scene originally entitled “Le Sommeil de Phrynette”, and his return to the family hearth and eventual forgiveness (“Le Retour”), combining two original scenes, “Le Retour” and “Le Pardon”. Carré’s L’Enfant prodigue has a rather special place in the history of French and European cinema because it was later the subject of one of the first “full-length” (1600m or about 80 minutes) film to have been made there. For a discussion of the further career of Michel Carré and the later film versions of his pantomime see my article “How the Cinema was Reborn in Dumbshow in 1907: Prodigal Sons and Shapely Calves”.

There was also a scene of mimed theatricals (“Le Piston de Hortense”) from the second act of a three-act comedy Ma Cousine by Henri Meilhac (1830-1897), created at the théâtre des Variétés on October 27, 1890 and starring one of the monstres sacrés of belle époque theatre, and the great rival of Sarah Bernhardt, Gabrielle Réjane (1856-1920). A hugely successful comedy – it ran for over two hundred consecutive performances – features the intrigues of a Paris socialite Gabrielle, played by Réjane, on behalf of her cousin Clotilde who is trying to win back her husband Raoul from his new lover, Victorine (here played by a certain Mlle Avril). The comedy contains a play within a play supposedly written by Victorine’s husband, Champcourtier and this play within the play begins with a pantomime (a comic polka). This scene, from Act II of the play, is a rehearsal of the pantomime which also features two actors called Lubas and Numa, presumably playing Raoul and Champcourtier, and the scene culminates in the polka, suitably accompanied by “lustful glances and jealous reproaches”, to quote the author of a modern adaptation of the Meilhac play, David Nicholson. Interestingly in Nicholson’s adaptation (updated to the 1920s), he has the rather good idea of having Champcourtier say that he does not call the dance scene (a tango in the updated version) a pantomime but is trying “to combine the best of moving pictures with the best of the stage. The curtains part . . . and the audience can read the preamble written on large cards – we call them titles – then the actors enter and, well . . . act – and the next title tells the audience what they are saying to one another, and so on, just like at the cinema . . . and then they dance a tango”. None of this could of course possibly have been said, or even thought, in 1900, let alone in 1890 when the play was written, but provides nevertheless a certain insight into the complicated reflexive relationship already involved in a film of a pantomime within a play. Réjane was less eager in general to perform for the camera than Bernhardt but would appear again for Le Film d’Art in 1908 and 1911 as well as starring in Henri Pouctal’s propagandist wartime drama, Alsace in 1916 and appearing in a small role in Louis Mercanton’s Miarka, la fille à l’ourse in 1920, the year of her death.

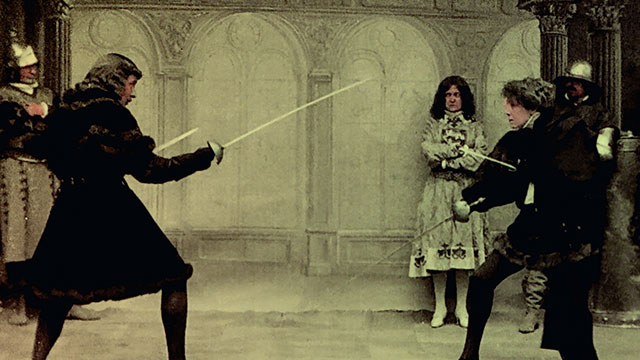

Sarah Bernhardt had her own theatre in the Place du Châtelet, the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt, where she was premièring L’Aiglon by Edmond Rostand during the Exposition, in which she played the title role of the hapless boy emperor Napoléon II (King of Rome) but for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, she reprised another “breeches” part, appearing in the duel-scene from Hamlet with Pierre Magnier as Laertes and Suzanne Seylor as “l’homme d’armes”. This part too was a relatively new one for Bernhardt, having been premièred at the same theatre on May 20, 1899 in a new, specially written prose adaptation in French of the Shakespeare play. Hers was very much a Hamlet in the Continental European style, portraying the character as a lively, active prince rather than as the self-pitying melancholic mother’s boy of the typical Anglo-Saxon reading, so the duel scene was a natural one to pick. In England, Hamlet tended to be dressed in black; even in France he traditionally wore a black-plumed hat, a tradition Bernhardt chose to discard. The black plume was inextricably associated with the graveyard scene and, by wearing an unadorned hat, Bernhardt liberated her Hamlet from the introspection, pessimism, and irresolution so often associated with the part. The British were of course scandalized by this “lack of proper philosophic melancholy” but the style became common in European performances and can be seen again in Asta Nielsen’s wonderful 1921 film of the Shakespeare play. Nielsen, although in fact Danish, was often described as “the German Bernhardt.”

The scene also shows off to best advantage Bernhardt’s legs in a costume deliberately designed to be more revealing in this respect than that of Pierre Magnier’s as Laertes. As Victoria Duckett has pointed out in her excellent Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film (2015), fencing was becoming a popular sport for women in France at this time. Nothing, according to La Vie parisienne in 1884, was “more efficient in combating this modern sickness of neurosis which they all more or less suffer, for accentuating the elegance of a slender waist, or for reducing the exaggerated opulence of the bodice.” It is not, however, Bernhardt’s legs nor even her acting that attracted most attention from the reviewers of this film in 1900-1902, but the unfamiliar and fascinating sound of the clashing blades as the two antagonists fight.

This film, was the beginning of a long involvement with the cinema for Bernhardt, who was one of the few stars of the classic theatre not to belittle the idea of “posing” for moving pictures, in the patronizing expression often used by stage actors, but to regard the new medium as a potential means of making a permanent record of at least some of her performances for posterity. It was a courageous posture for an artiste with such a formidable reputation at stake but Bernhardt did not hesitate to take the risk, appearing later in the title role of André Calmettes film of La Tosca (1908), based on the 1887 play by Victorien Sardou, a part she had herself first created on the stage in that year. In 1912 she appeared as the Queen in Henri Desfontaines and Louis Mercanton’s Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth (Queen Elizabeth) and as Marguerite Gauthier in Calmettes and Mercanton’s La Dame aux camélias (Camille). She appeared in four further feature films 1913-1917 and, despite her disability – she had had a leg amputated in 1915 and thereafter only played roles where she could remain seated – was in the process of making a fifth, La Voyante at the time of her death in 1924.

There was also a scene from Molière’s Les Précieuses ridicules (1659) with Benoît Constant Coquelin also known as Coquelin aîné (1841-1909). Coquelin, one of the most celebrated comic actors of the time, had first played the part of Mascarille, the servant who fancies himself a gentleman, in the Molière comedy at the Comédie française in Paris in 1875 but had also played the part more recently (1894) on Broadway at the Abbey’s Theater (later known as the Knickerbocker Theater). Here he appears with Mlle Marguerite Esquilar (born 1870) in the role of Magdelon and Jeanne Kerwich (dates unknown) in the role of Cathos, the two précieuses ridicules (affected ladies) of the title. The majority of this scene represented is in fact devoted to Coquelin (as Mascarille) singing an “impromptu” that he has composed, “Au voleur” (Stop thief!), which Coquelin sings extremely (but of course deliberately) badly.

Coquelin aîné also performed the duel scene from Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, a part he had created at the théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin (of which he was also the manager) at its première on December 28, 1897. We are extremely fortunate that this short film survives in color and with its original sound cylinder intact because these appearances are the only time that Coquelin ever deigned to appear before a camera. Maxime Desjardins (1863-1936), played Cyrano’s principal antagonist in the play (le Comte du Guiche) but is not in this film although he would go on to perform in some thirty films 1911-1932, while Kerwich, the ingenue whom Coquelin had recruited for his US tour, played Roxanne and would appear in three films, 1922-1930, including one of the first French “talkies” of the modern era, Ewald André Dupont and Jean Kemm’s Atlantic (Atlantis) (it was a Franco-British co-production) in 1930, where she and Desjardins, acting together on screen for the first and only time – they do not appear together in these films – play a man and wife traveling on the doomed liner (a simulacrum of the Titanic). Desjardins is mentioned in at least two programmes (when the show was on tour) but the character with whom Cyrano fights the duel in the play (and film) is not le Comte de Guiche but le comte de Valvert, de Guiche’s candidate for the hand of Roxanne, a part that was played by an actor (actress?) called Nicolini.

L’Ami Fritz (?)

One remarkable coup achieved by Marguerite Vrignault, if the “Le Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” poster is to be believed, more remarkable in its way than the presence in the show of Réjane, Bernhardt or even Coquelin, was to have enlisted the services of Suzanne Reichenberg. Suzanne, popularly known as “Suzette” – the famous crêpe flambée agave; la beurre Suzette created by Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935) was named after her at the suggestion of Prince Albert “Bertie” of England, the future Edward VII – Reichenberg (1853-1924) was “la plus parfaite des ingénues de la Comédie française” (the most perfect of the ingénues of the French Comedy) between 1870 and 1898, in the words of an 1885 tribute in Paris-Artiste, “une fleur, un sourire, un printemps” (a flower, a smile, a Springtime) according to Théophile Gautier, “aussi ingénue que fantaisiste” (as ingenuous as whimsical) according to the dandy Boni de Castellane, “toute gracieuse, habillée de rose pâle et coiffée d’un large chapeau blanc que couvre de grandes plumes roses.” (a picture of gracefulness, dressed in pale pink and a large white hat adorned with large pink feathers) according to Marcel Proust.

L’ingénue au théâtre, c’est l’adolescence accusant déjà la beauté qui va naître c’est la grace qui s’ignore, l’enjouement qui entraîne, la mutinerie provocante, la gaieté franche en dehors de toute préoccupation, la ferme assurance et l’aplomb décidé qui prennent leur source dans l’ignorance du mal, l’espièglerie qui blesse sans la savoir. Et bien, tout cela, Mlle Reichenberg le possédait lorsqu’elle fit ses débuts à’ la Comédie française, et elle en fait preuve encore tous les jours.

The “ingénue” in the theatre, is adolescence advertising the beauty about to be born; it is unconscious grace, enticing joy, provocative mutiny, frank gaiety devoid of all worldly concerns, firm assurance and resolute aplomb which have their origin in the ignorance of evil, a mischievousness that wounds without knowing it. Well, all that, Mlle Reichenberg possessed when she first appeared at the Comédie française, and gives evidence of it still every day.”

–Paris-Artiste No 20, 1885.

In 1886 she played Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet in a French adaptation by Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895) and Paul Meurice (1818-1905), a production where Jean Sully Mounet known as Mounet-Sully (1841-1916) in the title role, headed an all star cast that included the doyen of the Comédie française, Edmond Got (1822-1901) as Polonius, Georges Baillet (1848-1935) as Horatio, Eugène Sylvain (1851-1930) as Claudius, Marie Léonide Charvin known as Agar (1832-1891) as Guinevere and Ernest Alexandre Honoré Coquelin known as Coquelin cadet (1848-1909) as the gravedigger. In part inspired by Reichenberg’s performance, in part influenced by the pre-Raphaelite movement in England, the image of “Ophélie” became in the 1890s an iconic subject of French art and of the emergent post-Romantic French Symbolist movement.

Reichenberg, nicknamed “la petite doyenne”, had, however, retired from the stage in 1898 and would only return again to the boards, on one sole occasion, in 1910. If Vrignault had persuaded her to perform for a film in 1900, this was a distinct feather in her cap; Reichenberg certainly never appeared otherwise in any film.

Reichenberg played many parts in a stage career of thirty years, but one can nonetheless make a reasonable guess at the subject that would have been represented in a 1900 film, if it was indeed made. When she returned briefly to the stage in 1910 it was to play the part of Sûzel in L’Ami Fritz by Émile Erckmann (1822-1899) and Alexandre Chatrain (1826-1890), an 1876 dramatisation of their 1864 novel of the same name. The book and play are often said to be set in Alsace but the original setting is unspecified and is in fact more probably intended to represent the two authors’ native Moselle (in Lorraine). A rakish young man from a prosperous Jewish family, bon vivant and confirmed bachelor, Fritz Kobus, played in the stage production by Frédéric Fèbvre (1833-1916), is challenged by the skeptical rabbi David, played by Edmond Got, who is also the local marriage broker, and meets his match in the form of the innocent and beautiful young daughter of a local anabaptist farmer. The daughter, Sûzel, is of course played by Reichenberg and became her rôle fétiche (signature role). If she chose to reprise this role, despite her years, in 1910, it seems likely that this would also have been the role she would have chosen in 1900. Thanks to the play’s popularity and the plethora of publicity stills, it is possible to get a very good idea how such a film might have looked. L’Ami Fritz was filmed in 1920 by René Hervil with Léon Mathot as Fritz and Huguette Duflos as Sûzel and again in 1933 by Jacques de Baroncelli with Lucien Dubosq as Fritz and Simone Bourday as Sûzel.

There is, amongst all the contemporary documentation relating to the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” one brief mention of “mevrouw Reichenberg” in an announcement of the show when it was due to tour in Amsterdam in 1901 but this would seem simply to have been taken from the poster. During the actual run there, a long review was written which makes no mention at all of Reichenberg. So there is nothing either in the programmes or the reviews to comfort the idea that any film was actually made. Reichenberg was married on 12 October 1900, a major event in the Paris social calendar, to Napoléon-Pierre-Mathieu, baron de Bourgoing (1862-1953). It may well be well be that the approach of this marriage prevented the baronne-to-be from making the intended film. It is equally possible that a film was made but proved unsatisfactory for one reason or another.

Monsieur de Pourceaugnac (?)

If the Baronne de Bourgoing had come to the end of her distinguished career with the Comédie française, Maurice de Féraudy (1859-1932), whose name appears somewhat lower down in the cast list on the “Le Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” poster, was just beginning his. He had started at the Comédie française in 1880, become sociétaire in 1887 and would live to be the doyen in 1929. Although he had already made something of a name for himself, particularly in comic roles, it was not until a few years later (1903) that he would create his most famous role, that of Isidore Lechat in Les Affaires sont les affaires by Octave Mirbeau (1848-1914), a part he would play some 1,200 times in the next thirty years. He would go on to act in at least seventeen films 1908-1929 including Émile Chautard’s 1910 film version of Molière’s Le Médecin malgré lui, in which he played Sganarelle, Jacques Feyder’s Crainquebille (1922) in which he played the title role and René Clair’s Les Deux timides in which he played Thibaudier, the heroine’s father.

About this time Féraudy also embarked on an almost equally important parallel career as a parolier (songwriter). In 1900 he wrote the words for Amoureuse to waltz music by Rodolphe Berger (1864-1916). Sung originally by Marthe Jeanne Clémence Gallais known as Germaine Gallois (1869-1932) and later reprised by Pauline Josephine Combes known as Paulette Darty (1871-1939), it was his most successful song prior to Fascination, written specially for for Darty in 1905.

There are no references to any film featuring Féraudy in any programme or review, so, possibly, as in the case of Suzanne Reichenberg, none was made or any film that was made proved unsatisfactory. Unfortunately, when the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” films were brought to light for the first time, by Félix Mesguich in 1933, and efforts were made to contact and interview those who had been involved, Maurice de Féraudy was no longer alive. Evidently the intention cannot have been to make a film in which he played his role fétiche, as Isadore Lechat, but there is another interesting possibility to be found in the repertoire of the young actor. The comédie-ballet Monsieur de Pourceaugnac (1669) was one of the least performed of the works of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin dit Molière (1622-1673) even though, like Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (1670), it benefited from an original score by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), but the Comédie française decided to revive the play in February 1888 with the new sociétaire not in the title role but in the role of the apothecary who only appears relatively briefly in the play. Féraudy’s performance in this small part seems nevertheless to have caused a sensation and the critic Francisque Sarcey (1827-1899) described the occasion in Le Temps on 20 February 1888:

Féraudy n’a qu’une scène, celle où l’apothicaire offre ses services à Éraste. Il l’a bégayée avec un art exquis. Et comme elle est jolie, cette scène ! Je disais tout à l’heure qu’il n’y en avait qu’une dans l’ouvrage où se retrouvât la main de Molière. J’avais tort, en vérité : que d’autres dans Pourceaugnac, où l’auteur, sans rencontrer ce comique profond qui fait penser, abonde en saillies plaisantes et se joue en imaginations légères ! Y a-t-il rien de plus fantaisiste qu’Éraste courant embrasser Pourceaugnac et lui demandant des nouvelles de toute la parenté qu’il ne connaît pas ? Et cet apothicaire que joue Féraudy ! Cet apothicaire si parfaitement convaincu de l’efficacité des remèdes de sa médecine, quel type d’aveuglement et de bêtise ! Quels éclats de rire Féraudy a excités quand il a dit d’un air persuadé : « Voilà trois de mes enfants dont il m’a fait l’honneur de conduire la maladie, qui sont morts en moins de quatre jours, et qui, entre les mains d’un autre, auraient languiplus de trois mois. » Et, comme Éraste lui répond d’un ton d’ironie cachée, qu’il fait bon avoir des amis comme cela : « Sans doute, reprend-il. Il ne me reste plus que deux enfants, dont il prend soin comme des siens ; il les traite et les gouverne à sa fantaisie, sans que je me mêle de rien, et, le plus souvent, quand je reviens de la ville, je suis tout étonné que je les trouve saignés et purgés par son ordre. »

C’est tout à fait le genre de plaisanterie que nous aimons aujourd’hui, l’outrance dans le grotesque, qui est le fond de toutes les scies d’atelier à la mode. La supériorité de Molière, c’est que, sous ces imaginations fantasques, il y a un fond de vérité : que de gens ont la cervelle ainsi faite qu’ils sacrifient à un préjugé même ce qu’ils ont de plus cher.

Féraudy has only one [important – ed.] scene, that where the apothecary offers his services to Éraste. He stammered with exquisite art. And what an attractive scene that is! I said earlier that there was only one where one recognized the handiwork of Molière. In fact I was wrong: how many others there are in Pourceaugnac, where the author, without achieving that profound comedy that provokes thought, abounds in pleasant sallies and light, playful fantasy! Could there be anything more fanciful than Éraste running to embrace Pourceaugnac and asking him the news of all his family of whom he knows nothing? And this apothecary played by Féraudy! So perfectly convinced of the efficacity of the remedies and medicines; how blind and foolish! What gales of laughter Féraudy excited when he said with an air of conviction “See, three of my children whose sickness he [the doctor] has done me the honor of treating, dead in less than four days, when, in other hands, they might have lingered on for three months”. And how Éraste replies in a tone of disguised irony that it was good to have such friends. “Without a doubt, ” replies the apothecary, “I have only two children left and he takes care of them as if they were his own; he treats them and governs them as he thinks fit, without my being in the least involved, and, more often than not, when I return from town, I am astonished to find them bled and purged on his orders.”

This is absolutely the style of humor that we like nowadays, the grotesque taken to the limit that serves as a basis for all our fashionable, run-of-the-mill works of art. The superiority of Molière lies in the fact that, behind these weird fantasies, there is a basis of truth: that people have brains so made that they sacrifice to their prejudices even those that they hold most dear.”

Another celebrated drama critic, Adolphe Brisson (1860-1925) once described Monsieur Pourceaugnac as “L’Iliade des apothicaires” and it may be that the famous “scène de l’apothicaire” (acte I scène V but sometimes given as acte I scène VII) was originally intended to be included in the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” repertoire of 1900.

For the importance of this scene and this performance by Féraudy, I am much indebted to the article by Thierry Lefebvre, “Les Apothicaires de Monsieur de Pourceaugnac : trois types de représentation (1888, 1921, 1932)” in Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie (1989).

Opera

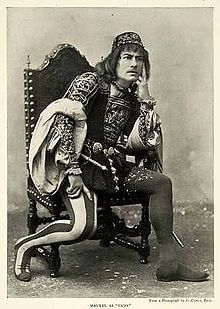

Arias from opera sung by popular stars were also a feature. The most important singer on the programme (his name appears just after Bernhardt and Coquelin on the original poster) was the baritone Victor Maurel (1848-1923). He made his Italian début at La Scala in Milan in La Traviata on 4 March 1868 and would become the favorite baritone of Giuseppe Verdi (1831-1901) in his later years. When his “grand opéra â la française”, Don Carlos, was given its Italian première in 1871, it was Maurel who was given the baritone role of Rodrigue rather than Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830-1914), who had first sung the part at l’Opéra in Paris in 1867 and when Verdi produced a second version of his 1857 opera Simon Boccanegra with a new libretto by Arrigo Boito (1842-1918), Maurel was given the title role in preference to the original Italian singer (Leone Giraldone). He also appeared at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden which is where he first played Don Giovanni in Mozart and Da Ponte’s 1787 opera, one of the signature roles that he would play almost every year, somewhere in the world, until 1899.

Maurel returned to France shortly afterwards and founded the Théàtre-Italien there in 1883, inaugurated with his own production of Simon Boccanegra, followed by Verdi’s 1844 operas Ernani, both featuring his pupil, the Russian-born soprano Françoise Jeanne Schütz known as Felia Litvinne (1860-1936). The theatre only survived for eighteen months, due to financial difficulties, and its demise left the singer/impresario feeling bitterly disillusioned:

“L’entreprise du Théâtre-Italien a versé, durant son existence, plus de sept millions dans le commerce parisien. Pour moi, qui y étais entré riche et désireux de m’employer pour le bien de l’art, j’en sortis pauvre et accablé sous le poids d’inimitiés et d’injustices de toutes sortes.

The enterprise of the Théâtre-Italien contributed, during its existence, seven million [francs] to the Paris economy. As for me, I started off rich but wanting to employ myself for the good of art, came out poor and burdened with the weight of enmity and injustice of all sorts.”

Maurel retained his association with Verdi and La Scala and it was this that would bring him international renown. On 5 February 1887 he created one of his most famous roles, that of Iago in Verdi’s Otello, enthusiastically reviewed by The New York Times when it played New York in December 1894:

Maurel’s Iago had not been heard here before last night, nor can it be said that the artist himself was at all well known by the public. It is twenty years since he visited America as a young man with only four years’ experience on the stage. He returns to us with some of the freshness gone from his voice – never a great one – but with his art at its maturity and backed by an authority which few operatic idols possess…[M. Maurel] was a revelation to the public of the resources that go to make the art of a truly great singing actor. His work last night was charged with vitality and significance. His vocal work was full of finesse and his acting was masterly. In a word, he gave a performance which justified his claim to the title of one of the greatest operatic artists of the day.”

On 25 May 1892 he created the role of the clown Tonio in the première of Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919) at the Teatro dal Verme in Milan under the direction of Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) but was back at La Scala on 9 February 1893 to create what was probably his most famous part of all, Falstaff in the opera of the same name by Verdi (his last opera) and Boito. The opera, a veritable masterpiece of adaptation by Boito, is drawn from the three Shakespeare plays in which the character appears, The Merry Wives of Windsor and the two parts of Henry IV (all c. 1596-1599) and the plot revolves around the thwarted, sometimes farcical, efforts of the fat knight, Sir John Falstaff, to seduce two married women to gain access to their husbands’ wealth. “Benissimo! Benissimo!”, Verdi wrote to his librettist in 1889, “no one could have done better than you”. It was the first Verdi opera for nearly six years and the performance, directed by Edoardo Mascheroni (1852-1941), was a huge success, ticket prices were thirty times greater than usual on the first night, attended by royalty and celebrities from all over the world and included the composers Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) and Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945). Applause at the end lasted nearly half an hour and the composer and his wife and librettist were given a tumultuous reception afterwards at Milan’s Grand Hotel. Maurel performed the part in Rome the following month, where the French press criticized him for the fact that he performed before an audience that included the German Kaiser, in Vienna in 1893, at l’Opéra-Comique in Paris (in French) in 1894, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1855 and at various venues during the US tour that followed, and, for the last time, at l’Opéra-Comique in Paris once more in October 1901, by which time the opera had curiously fallen into a certain neglect.

It is uncertain which aria he sang for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” but it was certainly from Falstaff. Neither the film nor the original cylinder survives and we cannot even be entirely certain that it was ever actually shown, as the only mention is in a programme, where it is simply listed among films promised for the following week. The programme in question would seem to have been produced quite late in the run; it mentions Friday gala performances which were only introduced when interest in the show seemed to be flagging. So presumably the film had been shown, which makes it puzzling that there is no reference to it in any reviews, suggesting that it was not, for some reason or another, a particularly satisfactory film. It does not appear to have figured later among the films taken on tour. A few years later Maurel would make several phonograph recordings, including arias from Don Giovanni, Otello and Falstaff. It seems likely that the short aria “Quand’ero paggio” (When I Was a Page) from Act II Scene II of the latter, which he recorded in 1907 for Fonotipia was also the one sung in the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” film. It is sung by Falstaff to Alice Page, whom he is trying to seduce, recalling his days as page to the Duke of Norfolk when he was young and passionate – an excuse for making unwanted advances – for which, as he puts it, “e non è mia colpa” (I am not to blame). “Se tanta avete vulnerabi polpi” (…if your considerable flesh is weak!), responds Mistress Page although he assures her he was slim in those days. Despite (or because of) its brevity and simplicity, it has always been a favorite aria from the opera.

The cavatina from Roméo et Juliette (1867) by Charles Gounod (1818-1893) and Jules Barbier and Michel Carré (libretto) was sung by a tenor from l’Opéra, Émile Cossira (1854-1823). With a certain inevitability it was the balcony scene, filmed in costume but without Juliet and with Cossira standing in front of a very modern-looking window. When the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” films, long thought lost, were rediscovered in the 1930s, those who recalled the events were invited to reminisce for the journal L’Image. Cossira’s son, Henry, recalled the awkwardness of the “playback” process, with the images seemingly being recorded immediately after the sound. He remembered his father spreading his arms wide to invoke the sun (“Lève-toi, soleil”) and singing aloud then remaining motionless to mime the words over again for the camera. Henry nevertheless judged that the synchronization was “not too bad for the period”. At the end of the performance, Cossira bows and then leaves the scene with a sly look back at the audience and, after leaving a suitable interval for applause, returns to take a second bow, as though he has been “bissé” (called for an encore). This was a device used several times in different ways during the show, and which one occasionally finds in later films – in Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth (1912) Bernhardt rises from the dead to take a bow – and its purpose was not simply to mimic theatre practice but to produce a sort of audience entrapment, whereby the cinema audience, applauding live, is surprised to see the characters on the screen seemingly responding to their reaction.

L’Invocation à Diane (“Ô toi qui prolongeas mes jours”) from Iphigénie en Tauride by Nicolas François Guillard (libretto) and Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) was sung by mezzo-soprano Jeanne Hatto (1879-1958). This famous opera, based ultimately on the tragedy by Euripides, had first been performed, in the presence of Queen Marie-Antoinette, on May 18, 1779, but was revived at the théâtre de la Renaissance in 1899 and at l’Opéra-Comique in 1900. Jeanne Hatto, just twenty-one, was a rising star at l’Opéra-Comique and in much demand; she would record the same song again for the Pathé Céleste, Pathé’s prize-winning new phonograph, the following year. The Annuaire des artistes for 1902 described her in positively adulatory terms:

Mlle Jeanne Hatto est actuellement, à l’Opéra, l’incarnation le plus parfaite du soprano dramatique. Grande, d’allure superbe, avec une physionomie d’une mobilité extraordinaire, ses yeux pétillants d’intelligence, et dans toute sa personne un air crâne qui en impose aux moins timides… elle est bien la femme pour personnifier, dans tout leur éclat, les héroïnes du répertoire lyrique.

Mlle Jeanne Hatto is at present, at l’Opéra, the most perfect incarnation of the dramatic soprano. Tall, with a superb bearing, and a physiognomy of an extraordinary unique mobility, eyes flashing with intelligence, and in all her person a brave air that imposes itself on the less timid [they mean presumably the opposite]…she is indeed the woman to personify, in all their splendor, the heroines of the lyric repertoire.”

Henri Cossira in 1933 recalled an anecdote told by the artistic director, Marguerite Chenu, of something that occurred when the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” was on tour in 1901. The cylinder for this particular film had been mislaid and Chenu and Félix Mesguich (responsible for the projection) were obliged to show it “silent”. Jeanne Hatto was, however, as it happened, herself in the audience, curious to see her own film, and Chenu held her breath and sent up a little prayer. Sure enough, at the appropriate moment, the song swelled loud and clear from the auditorium to the delight both of exhibitors and audience. It was one of those magical moments of “live” cinema, in a sense entirely lost to us today, that were always possible, whether by design or, as here, by happy accident, during the silent era.

In a rather different register, a lively trio from the second act of the popular operetta La Poupée (1896) by Maurice Ordonneau (libretto) and Edmond Audran (1842-1891) was sung by Belgian soprano Mariette Sully (1874-1940), who had created the role of the title character, Alesia, on the stage, with tenors Paul Fougère and M. Soums. This enormously popular operetta, which toured Europe for several years, is little known today but had an extremely important influence upon the history of cinema. It has a story not dissimilar to that of the famous conte by E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776-1822), Der Sandmann (1816-1817), in which an automaton comes to life. The Hoffman tale, a classic forerunner of so much later fantastique literature and films, had already been adapted as a ballet, Coppélia, ou la Fille aux yeux d’émail (1870), by Charles Nuittier with choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon and music by Léo Delibes. Edmond Audran’s operetta was a more light-hearted take on the same idea. A monk, Lancelot, played by Fougère, having promised to marry the daughter of his rich uncle Hilarius, played by Soums, to fool him into giving money to the monastery, creates a doll to replace the daughter. He is however outwitted by Hilarius and his daughter, Alesia, when she substitutes herself for the doll and obliges him to marry her. The operetta had opened at the théâtre de la Gaîté in Montparnasse, Paris on 31 October, 1896, played in London in 1897 for a staggering 576 performances and been partly filmed (three scenes) in Rome, during its Italian run, in 1898 or 1899, by Lumière operators, probably on the initiative of one of Lumière’s Italian “concessionnaires”, magician and quick-change artiste, Leopoldo Fregoli, who himself acted in it. Popular on the stage, such stories of automata and dolls that come to life have an even more striking analogical significance where the “moving pictures” were concerned. The operetta would form the basis for a later Lumière film (1903), Les Poupées by Gaston Velle, would be filmed in Britain by in its entirety by Ward Meyrick Milton in 1920 as well as providing the inspiration for Ernst Lubitsch’s 1919 comedy Die Puppe.

Fleur de l’âme – Pourquoi garder ton coeur ? – Après la bataille

Duo Mily-Meyer et M. Pougaud – J’ai perdu ma gigolette *

(* indicates lost film)

Soprano Émilie Mily-Meyer, also known as Mily-Meyer (1852-1952), was something of a hybrid, who lent her powerful voice both to innumerable operettas and to songs and sketches in the café concerts. The songs performed in 1900 came principally from a show called Chansons en  crinoline that she performed with Désiré Cousin known as Désiré Pougaud (1866-1928) at the théâtre du Châtelet. There were two solo songs under this general title – Fleur de l’âme, a setting by Joseph Vimel of the untitled Victor Hugo poem “Puisque j’ai mis ma lèvre”, and Pourquoi garder ton coeur ?, a very charming 1886 song by Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin (1821-1910), J. Leybach, and Victor Wilder, but one of them (it is not certain which) had to be withdrawn after Mily-Meyer received complaints that a couplet was missing that rendered the song incomprehensible. A contemporary recording exists for Fleur de l’âme but is in fact a re-recording for the Pathé Céleste, suggesting this may have been the film dropped from the original show but reinstated some time after September. There were also two untitled duets with Pougaud. Neither of these cylinders appear to survive and only one of the films survives in an incomplete version. According to the Gaumont/Pathé archives, who possibly possess a still, both films show Mily-Meyer and Pougaud in the same costumes and in the same garden setting. The extant duet does not seem to be a duet as such – there is no sign of Pougaud doing more than beating time on his hat – and, to judge from the hand gestures, is in fact “La Chanson du tambour-major” from the three-act operetta Les Voltiguers de la 32ème (1880, Théâtre de la Renaissance) by Robert Planquette (1848-1903) with a libretto by Georges Duval (1847-1919) and Edmond Gondinet (1829-1888). This and another operetta produced by Planquette in the same year, La Cantinière, were military comedies produced to cash in on the success of the previous year’s La Fille du tambour-major by Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880), itself influenced by Gaetano Donizetti’s French opera La Fille du régiment (1840). The Planquette operetta is set in a fantasy Napoleonic France where the old wounds of the revolution are being healed by romance and marriage between the soldiers of the grande armée and the members of the ci-devant aristocracy.

crinoline that she performed with Désiré Cousin known as Désiré Pougaud (1866-1928) at the théâtre du Châtelet. There were two solo songs under this general title – Fleur de l’âme, a setting by Joseph Vimel of the untitled Victor Hugo poem “Puisque j’ai mis ma lèvre”, and Pourquoi garder ton coeur ?, a very charming 1886 song by Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin (1821-1910), J. Leybach, and Victor Wilder, but one of them (it is not certain which) had to be withdrawn after Mily-Meyer received complaints that a couplet was missing that rendered the song incomprehensible. A contemporary recording exists for Fleur de l’âme but is in fact a re-recording for the Pathé Céleste, suggesting this may have been the film dropped from the original show but reinstated some time after September. There were also two untitled duets with Pougaud. Neither of these cylinders appear to survive and only one of the films survives in an incomplete version. According to the Gaumont/Pathé archives, who possibly possess a still, both films show Mily-Meyer and Pougaud in the same costumes and in the same garden setting. The extant duet does not seem to be a duet as such – there is no sign of Pougaud doing more than beating time on his hat – and, to judge from the hand gestures, is in fact “La Chanson du tambour-major” from the three-act operetta Les Voltiguers de la 32ème (1880, Théâtre de la Renaissance) by Robert Planquette (1848-1903) with a libretto by Georges Duval (1847-1919) and Edmond Gondinet (1829-1888). This and another operetta produced by Planquette in the same year, La Cantinière, were military comedies produced to cash in on the success of the previous year’s La Fille du tambour-major by Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880), itself influenced by Gaetano Donizetti’s French opera La Fille du régiment (1840). The Planquette operetta is set in a fantasy Napoleonic France where the old wounds of the revolution are being healed by romance and marriage between the soldiers of the grande armée and the members of the ci-devant aristocracy.

Despite a fine cast, the soprano Jeanne Granier (1852-1939), the baritone Jean-Vital Jammes known as Ismaël (1825-1892) and Marie Desclauzas (1841-1912) as well as Mily-Meyer herself, the operetta enjoyed only moderate success in France (seventy-three performances however), but in London, where it played as The Old Guard in an English adaptation by Henry Brougham Farnie (1836-1889), it had, thanks largely to a performance by comedian Arthur Roberts (1852-1933) as Polydore Poupart, a long run at the Avenue Theatre in 1887.

The music, however, seemed to have a life of its own. The entire score was transcribed for piano and singer by the composer Alfred Fock (1850-1921) and also reissued as three piano suites, Bouquet de mélodies sur ‘Les Voltigeurs de la 32ème’ by “Cramer” (music-publishers’ pseudonym). There was a piano transcription of the “Quadrille” from the operetta by Gilles Raspail (died 1889) that ran to four editions 1800-1883 and a setting of this song, “La Chanson du tambour-major” for military band (1886) by Michel Bléger (d. 1897). There were also versions of several other pieces from the operetta transcribed for brass band (fanfare).

Jeanne Granier, in the role of Nicolette, provided the love interest opposite Ismaël as le marquis. The matronly Desclauzas played Dorothée while Mily-Meyer had played le sergent Flambard in the original show, a child drummer boy – the equivalent in the English version was the bugler Patatout – who seems to spend some of the time en travesti as a young girl (a girl playing a boy disguised as a girl). The rendition of the song (if so it is) by the mature Mily-Meyer for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” in 1900, perhaps in a later transcription, must evidently be a little different from the original, but does seem nevertheless to match fairly closely with the music. Pougaud was once (1895) described by a critic as “ce boute-en-train rempli de malice et de fantaisie qui a nom Désiré Pougaud” (madcap full of malice and fantasy). Pougaud, a songwriter and actor as well as a singer, would later (1916) appear in two films, Chantecoq and L’Instinct directed by Henri Pouctal.

Later in the run of the show and during the tours that followed, Mily-Meyer is advertised generally as singing Chanson en crinoline in the singular and it would seem therefore that one of the solo songs – presumably whichever was missing a couplet – and the two duets were all dropped from the show. There is an extant film, said to have been made for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” of a young woman singing Après la bataille, which is not a setting of the famous Victor Hugo poem of that name but a rousing patriotic song. The film is shot outdoors with a painted background representing a village. As with the Mily-Meyer Duo, the woman is elegantly dressed and there is no attempt to reproduce a military atmosphere beyond a certain dash in the singer’s movements. A contemporary recording exists, made for the Céleste, of Mily-Meyer belting out this song but she was now forty-eight and is clearly not the woman in the film. Conceivably a younger actress was used and the sound dubbed but this was not done for the Duo, also a young girl’s song, or for any of the other “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” films and it seems extremely improbable that they would have done this in the case of Mily-Meyer, who was one of their leading artistes. In all probability, whether sung by Mily-Meyer or by a young woman with a particularly robust voice that greatly resembles that of Mily-Meyer, this was made by Pathé itself, also involved in making “talkies” at this time, and not for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”.

Amongst the few films in the repertoire that remain missing is the comic song, J’ai perdu ma gigolette sung by Louis Maurel (1859-1936), Maurel was a talented café concert performer but also an actor. He would make an appearance (as himself) in a Georges Méliès film in 1905 (Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en deux heures) where several other celebrities appear, including Little Tich, and he would also play small parts in two later films (1917 and 1935). His sister Rosine (1850-1919), also a singer and actress, appeared in three films 1913-1938. This comic song, written by Lucien Delormel (music), René Esse and Félix Mortreuil in 1892 and performed by Maurel at l’Alcazar, does itself survive in a later recording.

Comic Monologues

Le Maître de ballet – Une poule introduite dans un concert

J’ai le pied qui remue * Concert arabe *

Jules Moy (1852-1938), a performer at the famous cabaret Le Chat Noir and a comedy actor who would go on to appear in several films 1916-1936, performed comic monologues, of which only two survive as films, Le Maître de ballet and Une poule introduite dans un concert. Le Maître de ballet, where he plays an irritable music master who is so annoyed with his pupils that he erupts in a fit of coughing, proved one of the show’s most successful films, partly because it made particularly good use of the accompanying sound. A contemporary recording does also exists for the first of these but, like most of the surviving cylinders, it is a later recording made for the Céleste. The two readily identifiable theatre posters that adorn the ballet master’s walls are both surprisingly English, one being a poster for His Majesty, or, The Court of Vingolia, a two-act comic opera by F.C. Burnand that ran at the Savoy Theatre (famous for the D’Oyley Carte company’s performances of the work of Gilbert and Sullivan) from 20 February-21 April 1897 and the other a lithograph for George Arliss’ The Wild Rabbit, a farcical comedy that played at the Criterion theatre in London from 25 July to 18 August 1899. One German reviewer, when the show was on tour, thought Moy in this role “typical of a vivacious Frenchman” but perhaps he is supposed to be English. Moy was also responsible, according to the Gaumont/Pathé archive site, for a third monologue, Concert arabe, for which both film and cylinder are lost. A recording also exists for another Moy monologue, largely sung after a fashion, J’ai le pied qui remue, but this was more probably a later recording for Pathé and had nothing to do with the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”.

Moy was able to surprise journalists in 1932, in replying to a question as to when he had made his first film by announcing that it had been in 1900 and a “talkie”. He also explained the difficulties associated with the as yet un-automatized playback synchronization.

Oui, j’ai tourné mon premier film sonore à l’Exposition de 1900. Ça s’appelait le “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”. Il fallait s’habituer à parler en même temps que les images passaient. Quand on avait peu de choses à dire ça allait. Mais quand il fallait “synchroniser” (le mot n’existait pas encore) une longue tirade, ça n’allait plus du tout.

Yes, I made my first sound film at the Exposition of 1900. It was called the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”. One had to get used to speaking at the same rhythm as the images that were shown. When one didn’t have much to say, that was fine. But when one had to “synchronize” (the word didn’t exist yet) a long tirade, that didn’t work at all.”

The point made by Moy here explains a great deal about the repertoire of the early “talkies” and why they almost invariably tended to privilege scenes of song and dance over the spoken word. The latter was simply far more difficult to synchronize. Unsurprisingly the pioneers who ventured furthest with the spoken word were those, like Auguste Baron and later Henri Joly, who had devised an electrical device to create an automatic link between cinematograph and phonograph. Yet even when this process was generally automatized (after 1907), the prejudice in favor of song and dance remained. It was perhaps the greatest weakness of these early “talkies'”. Essentially film-producers labored under a misconception that it was these aspects of sound that must necessarily be most interesting to audiences. It rarely occurred to them – and it is perhaps counterintuitive – that is was the perfectly ordinary spoken voice that they were principally interested in hearing. Even after 1927-1928, and despite the sensation caused by the famous incidental piece of well-worn Jolson stage patter in the part-talkie The Jazz Singer (“you ain’t heard nothing yet”), the misconception persisted, as witness the excessive number of musicals produced in 1929-1930, many completely abysmal, which came close to making the public thoroughly sick of the “sound” revolution they had so enthusiastically welcomed.

More “spoken word” was provided by French café concert comedian and singer Paul Marsalés also known as Polin (1863-1927) who performed a comic monologue, Le Troupier pompette. This genre, the “troupier comique” (the comic soldier), was a Polin speciality derived from the many comedies of military life written at the end of the nineteenth century by Georges Courteline (1858-1929), of which the most enduringly famous is the 1886 comedy, filmed many times over the years, Les Gaietés de l’escadron. In 1906 Polin would, along with fellow café concert stars Félix Mayol and Dranem, record for both camera and phonograph a whole series of “phonoscènes”, a lucky thirteen in all, in what amounted to a kind of “best of” compilation (“Polin dans ses créations”) and an effective film-record of the singer’s career.

Dance

Although the theatrical pieces produced for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” were sensational enough, it was in some respects the remarkable dance program that was the highlight of the show. Like the great and the good of the legitimate theatre, the major dance stars tended to turn their noses up at cinema; even Alice Guy at Gaumont, who showed a very particular interest in dance films from an early stage in her career, had to rely largely on dancers of second rank. Here Vrignault has managed to assemble a really rather remarkable lineup of first-rate stars. The Italian Achille Viscusi (1869-1945) was not only a dancer but one of the most important choreographers and dance teachers of the day, as was Jeanne Chasles (1869-1939), director of l’Opéra-Comique and later (1915) professeur de danse at the Paris Conservatoire. The Belgian Joseph Hansen (1842-1907), who choreographed one of the ballet scenes, had worked in London and Moscow before becoming Maître de ballet at the Palais Garnier (1887-1907). Michel Vasquez (1855-1903) was later Maìtre de Ballet at l’Opéra (1902-1903).

Christine Kerf (1875-1963), a star at l’Opéra-Comique, would go on to appear in four films (1912-1922). The Spanish dancer Rosetta Mauri Segura (1850-1923) was approaching the end of her career – she had actually retired from dancing in 1898 – but would teach at l’Opéra until 1920. She was succeeded in her roles by the Italian Carlotta Zambelli (1875-1968), who would go on to be one of the great stars of l’Opéra, later known as “la Grande Mademoiselle”, and who would leave in 1901 for a tour in St. Petersburg. Zambelli herself retired from dancing in 1930 but taught for a further twenty-five years, a career at l’Opéra of sixty-one years in all. According to dance critic André Levinson (1887-1933), Zambelli exemplified “la ferveur italienne, tempérée par la mesure française” (Italian fervor tempered by French rhythm), which produced

une exécution pondérée, nuancée et infiniment vivante… Son jeu est aigu, incisif, brillant ; ses pas ne sont pas ébauchés à l’estompe, mais tracés au burin. Aucun excès de sensibilité, mais infiniment d’intelligence… Ce qui enrichit l’art subtil de Carlotta, fait d’intuition et de discipline, d’un attrait exceptionnel sinon unique, c’est sa suprême musicalité, c’est la naissance de chaque pas de l’esprit même du rythme, la concordance absolue de l’impulsion sonore et de l’essor saltatoire.

a performance, deeply considered, nuanced and infinitely lively ….sharp, incisive, brilliant; her steps are not produced with a stump but traced with a fine engraving tool. No excess of sensibility, but an infinity of intelligence….What enriches Carlotta’s subtle art, formed from a combination of intuition and discipline, of an exceptional if not unique attractiveness, is her supreme musicality; it is the birth at each step of the spirit of rhythm itself, the complete concordance of the impulse of sound with the sweep of her curvet.”

A pupil, Lycette Darsonval (1912-1996), later herself directrice of the ballet de l’Opéra and of the ballet de Nice, once said of “la Grande Mademoiselle” that she taught dancers “à n’être pas que des automates” (not just to be automata) “mais à pénétrer aussi l’esprit d’un ballet, à observer les jeux de l’expression.” (but to penetrate the spirit of the ballet, to observe the play of expression).

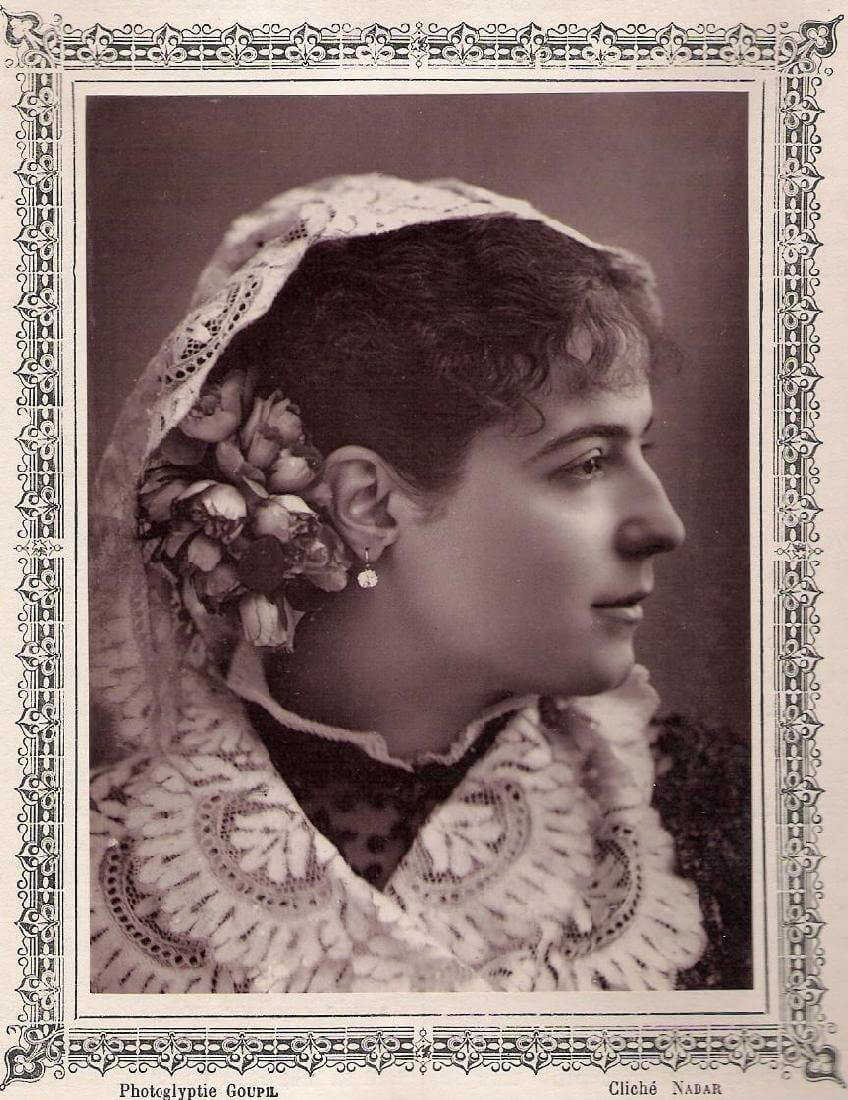

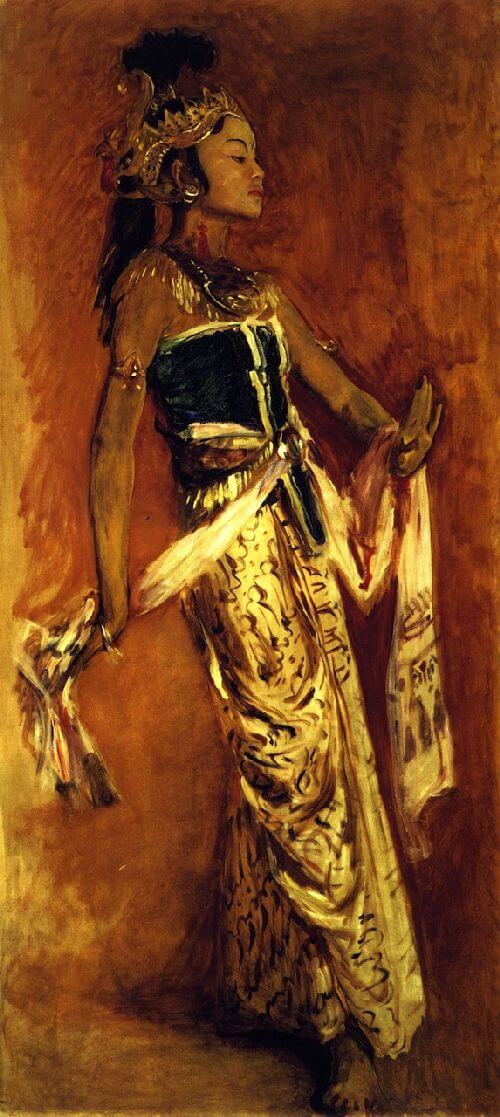

The program also included a performance by Cléo de Mérode who was something else again. Cléopâtre-Diane de Mérode, also known as Cléo de Mérode (1875-1966), was not only a dancer but one of the acknowledged beauties of the period. Already by the age of twenty-three, in 1898, she had danced in the major works of Delibes (Coppélia and Sylvia), André Messager (Les deux pigeons), André Wormser (L’Étoile) and Gustave Charpentier (Le  Couronnement de la Muse) but had left l’Opéra in that year to pursue an independent career. Her reputation as a dancer was often eclipsed by her mythic status as “reine de Beauté” (beauty queen) established notably in a series of photographs by Paul Nadar (1856-1939), son of the more famous Félix Nadar (1820-1910), and Léopold-Émile Reutlinger (1863-1937), whose sumptuous albums of photographs devoted to her gained an international reputation and spawned innumerable postcards. A great many of the photographs, including those of her in costume for both her Javanaise and Cambodian dances, were taken at precisely this time.

Couronnement de la Muse) but had left l’Opéra in that year to pursue an independent career. Her reputation as a dancer was often eclipsed by her mythic status as “reine de Beauté” (beauty queen) established notably in a series of photographs by Paul Nadar (1856-1939), son of the more famous Félix Nadar (1820-1910), and Léopold-Émile Reutlinger (1863-1937), whose sumptuous albums of photographs devoted to her gained an international reputation and spawned innumerable postcards. A great many of the photographs, including those of her in costume for both her Javanaise and Cambodian dances, were taken at precisely this time.

Scandal had been caused by a famous nude statue (1896) of Mérode by Jean-Alexandre-Joseph Falguière (1831-1900), although she denied ever having actually posed nude for it. Then there were the risqué performances at the Folies Bergère and the Alcazar, a far cry from le ballet de l’Opéra, and the seemingly endless procession of male admirers, including most notoriously King Léopold II of the Belgians, with whom equally she denied ever having had an affair, as was popularly rumored. All served to give her at this time a particularly sulfurous reputation on a par with that of the other celebrated dancer-courtesan of the Belle Époque, the Spaniard Caroline Otero (la belle Otéro) (1868-1965), a reputation which, although it added to her celebrity, was mercilessly exploited by the caricaturists. Yet, although the two were often popularly seen as rivals, they had in reality little in common. Unlike the flamboyant and opportunistic Otero, Cléo de Mérode took her dancing, even if it became of a distinctly eclectic nature, perfectly seriously and, again unlike Otero, always denied the imputations alleged by her detractors. As late as 1955 she would successfully sue Simone de Beauvoir after the feminist had sourly referred to her as a “cocotte” in her 1949 book Le Deuxième Sexe.

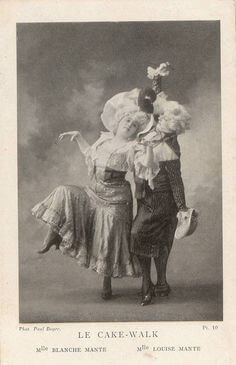

Other dancers who appear, minor only by comparison with the big stars, were the three dancer-daughters of Louis-Amedée Mante, Suxanne, Louise (1880-1999) and Blanche and Sandrine Violat, all of whom were regular dancers at l’Opéra. The Mante sisters were known punningly as “Mantes-les-Jolies” because of the town of Mantes-la-Jolie, now a very unpretty suburb in the Paris sprawl. Described as danseuses mondaines (social dancers), they would later record several “phonoscènes” for Alice Guy at Gaumont in 1906. Louis-Amedée Mante (1826-1913), himself appears nowhere in the program and is not amongst the credits, but it does not seem too fanciful to suppose that he may have played a certain role in its evolution. Bass player with the orchestra of l’Opéra, he was also a celebrated photographer. The Mante sisters were not only frequently photographed by their father but also painted by Edgar Degas (1824-1917), who had known them from childhood.

As regards the content of the program, it is as remarkable for what it does not contain as for what it does. There is for instance no “Loïe Fuller” dance, what would later be thought of as “modern dance”. Apart from the British, who seem at this time to have had little concept of dance beyond jigs and highland flings, virtually every filmmaker of the period from Max Skladanowky in Germany to Lumière, Pathé, Demenÿ and later Guy for Gaumont, Méliès, Parnaland, Joly, Léar and Pirou, Mendel, Baron, Nadar, De Bedts and, across the Atlantic, Edison, Mutoscope, Lubin and Selig, all eagerly jumped on the bandwagon of Fuller’s surprise success at the Folies bergère (the danse serpentine of 1892) and produced at least one example, and often several examples, of some dancer or other – never Fuller herself – twirling around in a flurry of bedsheets. Given the constant parade of such Fuller dance-alikes, the omission here is very striking and must quite clearly be the result of a deliberate decision not to include such a film. Fuller was, however, herself to be seen live at the Exposition, in company with a troupe of Japanese dancers, at the art nouveau théâtre de la Loïe Fuller that she had had specially constructed by architect and designer Henri Sauvage (1873-1932).

Then again, although the program is, as we shall see, far from austere or lacking in passion and sensuousness, and contains much exotic and “orientalist” material, there are no belly dances or spear-waving Ashanti. There are no Barrison sisters, the “wickedest girls in the world” offering to show the audience their pussies; they had kittens strapped into their knickers. There are not even any of the popular novelty dances (the cakewalk, the kickapoo, the tough dance, the apache dance, the shimmy), that were beginning to become popular in the US and would in time come to dominate the dance repertoire of films. Instead what we have is a high quality program of an interesting variety but of a certain artistic seriousness that is enormously to the credit of Marguerite Vrignault, herself a dancer, as director. It is also in looking at the dance program that one appreciates fully the way that the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, situated itself at the heart of the Paris Exposition, sought to develop the “cosmopolitan” themes and motifs associated with the International Expositions.

The Palais de la Danse advertised itself at this time as providing “a history of the dance in ballets” with “dances from all countries”. Terpsichore was a new one-act ballet produced in 1900 with music by Léo Pouget (1875-1930) and a libretto by Adolphe Thalasso (1858-1919), choreographed by Mariquita and, in the original production, with an orchestra directed by Félix Desgranges. Marie-Thérèse Gamalery, also known as Madame Mariquita (1841-1922), was an Algerian-born dancer of Spanish descent who had a remarkably varied career and was quite possibly the most famous maîtresse de ballet of the Belle Époque. She had made her début at the Funambules, in the dingy boulevard du Temple (nicknamed “boulevard du Crime”, later famous as the setting for Marcel Carné’s Les Enfants du paradis), then worked her way up successively to théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, the Teatro Variedades in Madrid (where she presumably learned the flamenco), théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin (whose director, Marc Fournier, she married). By 1871 she was maîtresse de ballet at the Folies bergère but continued to dance herself in theatres of all kinds (Châtelet, Gaîté, Bouffes-Parisiens, Variétés, Porte Saint-Martin, the London Lyceum, the théâtre Lafayette in Rouen, the Skating de la Rue Blanche, etc.). Maîtresse de ballet at l’Opéra-Comique (1898-1920), in addition to her work at the Folies, she was also director of choreography of the Palais de la Danse at the 1900 Exposition. This did not prevent her from also dancing herself from time to time, during the Exposition, at “La Feria” restaurant in the Spanish Pavilion in the Rue des Nations.

The entire ballet consisted of three separate tableaux, each representing a different country – Spain, Italy and Greece. Un mariage aux flambeaux, danced by Christine Kerf and Achille Viscusi for the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, set in the Alhambra at Granada, was the Spanish scene, featuring characters based on Carmen, Kerf as “la cigarrera” and Viscusi as a matador while the dance itself was a flamenco. Le Matin, which had reviewed the stage show on 27 May 1900, singled Kerf out for praise for “l’élégance et la fureur” (the elegance and fury) of her performance, describing her as “une danseuse étonnante” (an amazing dancer). An extended article by critic Gabriel Pitté consecrated to Terpsichore in La Grande Vue provides a fuller account:

Tout en satin blanc, une fabricante de cigares se penche, brille, tourbillonne et s’enflamme, poursuivie et hantée par un torero agile, un torero tout en satin blanc comme elle et qui, vertigineux, plein de désir passionné, tremble frénétiquement sous ses jupes un tambourin tintant. Presque accroupi sous ses pas, on dirait qu’il infuse la montée de son désir ardent : la fabricante de cigares, après chaque pause, se penche de plus en plus abandonnée, puis se lève et repart, volant au-delà. Six Andalouses vêtues de longs châles, la fleur de la grenade à l’oreille, rampent dans leur ombre, les suivent pas à pas, enivrant le couple avec un tumulte déchaîné d’olés, de tambourins et de gais castagnettes : au fond, au fond des arches maures, les guitares étincelantes et les torches qui rougissent, saignent dans le bleu de la nuit : c’est toute l’Espagne et tout Grenade.

All white satin, a cigar maker leans, shines, swirls and flames, pursued and haunted by an agile bullfighter, a bullfighter, all white satin like her, who, dizzyingly, full of passionate desire, frantically shakes beneath her skirts a tinkling tambourine. Almost crouching under her feet, he could be said to be infusing the mounting ardor of his desire: the cigar maker, after each pause, leans in with more abandon, then gets up and leaves, flying away. Six Andalusian girls dressed in long shawls, with pomegranate flowers in their ears, creep in their shadow, following them step by step, intoxicating the couple with a raging tumult of olés, tambourines and cheerful castanets: in the background, behind the Moorish arches, the jangle of guitars, and the glowing torches that bleed in the blue of the night: it is all Spain and all Granada.”

For the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre” version it would seem from Pitté’s account that the six Andalusian dancers were replaced by an entire corps de ballet specially imported from Granada so that “leurs coutumes quelque … dangereuses” (their somewhat…risqué costumes) “pour être exposés avec toute la fougue de la jeunesse devant les regards excités d’un public cosmopolite” (could be displayed with all the élan of youth, before the excited regard of a cosmopolitan public). This show in full could also be seen live at the Palais de Danse in the Rue de Paris, just a short walk away.

Le Cid was a four-act opera rather than a ballet, with music by Jules Massenet (1842-1912) and a libretto by Louis Gallet, Édouard Blau and Adolphe d’Ennery based on the 1636 play by Pierre Corneille, but it gives a very large place to dance, with an elaborate ballet suite in Act II. The part of the suite danced was described as a “habanera” but there is in fact no “habanera” in the opera, but rather a “Castillane”, followed by an “Andalouse”, an “aragonaise”, an “aubade”, a “Catalane”, a “Madrilène” and a “Navarrosie”, the object being in other words to represent all the different regions of Spain. First produced by l’Opéra-Comique, the ballet suite had been specially created by Massenet for the Spanish prima ballerina Rosita Mauri, who was now, almost symbolically, passing on her roles to Carlotta Zambelli. The original cylinder does not survive but what Zambelli and Michel Vasquez dance is in fact the “Pas de la Castillane” (correctly identified in other programmes for the show).

Map showing locations where Spanish Dances were performed at the Exposition. Image courtesy of Kika Mora, La Boîte Verte, and Grimh.org.

The Kerf-Viscusi flamenco and the Zambelli-Vasquez “Pas de Castillane” constituted only a small part of the Spanish dance available at the Exposition. An Andalouisan dance troupe could also be seen in L’Andalousie au temps des Maures at the Trocadéro while other Spanish dancers featured in the Panorama de La Tour de Monde at the Théâtre Exotique in the Champ-de-Mars, at the “La Feria” restaurant in the Spanish Pavilion in the Rue des Nations and, from time to time, at the Pavillon Bleu in the shadow of the Tour Eiffel. There was apparently even a spectacle Las sevillanas being performed in the reconstructed “Vieux Paris” along the banks of the Seine.

Japanese art was in high esteem in France at this time. The Japanese “ukiyo-e” (floating world) art movement that had flourished under the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868) was an important influence on the Impressionists and other contemporary French painters. High prices were paid for very collectable works by Outamaro and Hokousai to whom the writer and critic Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) had devoted books in 1891 and 1896. In 1889 Le Guide Bleu du Figaro et du Petit Journal enthused over the Pavillon japonais – “des soieries, des porcelaines, des cloisonnées, des laques, des sculptures. Mille richesses arrêtent retiennent” (silks, porcelains, partitions, lacquers, sculptures. A thousand riches retain the attention) and the art historian Raymond Koechlin (1860-1931), visiting the pavillon japonais in 1900, regretted the “egotistical classicism” of certain Europeans that was all that prevented Japanese (and for that matter Chinese) art from taking the place alongside European art which was rightfully theirs.